America's Ingratitude for Its Naming:

The Tribulations Signora Vespucci

by Allen Walker Read

One of the most fascinating women in America in the mid-nineteenth century was Signora America Vespucci who came to this country to claim land as a benefit of her descent from the explorer for whom the continent was named. Much has been written about her as the toast of Washington in the late 1830's and, especially, of her life as a chatelaine of George Parish, in whose mansion in Ogdensburg she was secluded for twenty years. The fictional account by Walter Guest Kellogg, entitled Parish's Fancy is well known to many Quarterly readers. Here a distinguished linguist and scholar of the history of names (onomastics) reveals his discoveries in numerous original sources that shed new light on this interesting personality.

If one were to ask for an episode in American naming history with remarkable romantic overtones, one need go no farther than the story of Signora Ameriga Vespucci, who came to this country in 1839 in order to receive benefit because of her descent from the explorer for whom the continent was named.

She was not an imposter, for she truly was a member of the illustrious Vespucci family of Florence and a direct descendant of Amerigo, bringing with her impressive credentials from the Court of France, where she had been living. She also had the blessing of the French legation in Washington. However, wild tales about her were soon in circulation, many of them of her own manufacture.

She arrived in Washington, D.C., on January llth, 1839, and the correspondent of a New York City newspaper sent back the following dispatch:

Last evening arrived in this city, that distinguished and accomplished lady America Vespucci said to be a daughter of the illustrious house of Vespucci of Tuscany. According to accounts which we have received here, she is a lineal descendant of him, after whom our country has received its name, instead of Columbus. What is the object of her visit I am uninformed, but rumor says she would honor us with the acceptance of a state or territory, if we should think it expedient to make the cession. "Hail Columbia, happy land." [N. Y. Morning Courier and Enquirer, Janu-ary 14.1839, p. 2, col. 4.1 ]

As the dispatch said, rumor was swirling about her. She was an impressive woman, beautiful, charming, vivacious, and accomplished; and she soon made many friends among the senators and important people of Washington. Even Martin Van Buren, the courtly, decorous President, was impressed. As he was a bachelor, it was rumored that he might develop a romantic attachment.

There were many testimonials to her remarkable personality. A member of the British Parliament, James Silk Buckingham, was traveling in this country, and in his travel book of 1842 he wrote down the following impression of her:

In person, she had the style of beauty which one sees in the finest statues of the antique- a noble head, regular and expressive features, a fair and stately neck, dark eyes, dark hair, beautiful lips and teeth, a fine expanded chest, well-rounded arms, white and delicate hands, small feet, and an exquisitely graceful figure of the middle size. She appeared in a simple yet elegant and well-made dress of black silk, trimmed with blue lace. Her head was marked by a classic grandeur, though without any kind of ornament but her rich and exuberant hair: her voice was full of music: and in her look and expression, dignity and sweetness were happily blended. Her age appeared to be about twenty-five or twenty-six, and her whole deportment presented the most agreeable combination of dignified self-respect with refinement, polish, and ease, that I ever remember to have witnessed.

He finished his encomium by writing:

It is not too much to say of her, that there is no throne in Europe, which she would not elevate by her wisdom: no court which she would not adorn by her manners; no family, that she would not delight by her conversation: and no man, however noble in birth, profound in erudition, high in station, or opulent in fortune, to whom she would not be a source of intellectual and social enjoyment, if he could but win her respect and confidence, and become the object of her esteem as well as of her affections. [James Silk Buckingham, The Slave States of America (London, 1842). I, 392 and 394. The interview took place in New Orleans.]

She made a similar impression on the American poet Nathaniel P. Willis, a notable man-about-town and bon vivant. He wrote these verses—

TO AMERIGA VESPUCCI

Blest was thy ancestor with deathless fame,

When to this western world he gave his name:

But far more blessed, methinks, that man would be,

Fair scion! who might give his name to thee.

The tale she told of herself was that she had been a fighter for liberty in the wars to free the states of northern Italy.

The following is the account in the

In the attempted rising of August, 1832, and in the engagement with the Austrians on the banks of the Rimini, in which it will be remembered by our readers that young Louis Bonaparte took part, she conducted herself with great gallantry, and received a severe sabre stroke on the back of her head, from an Austrian dragoon (to whom, however, though nameless, the justice ought to be done to state that he did not know her to be a woman;) and in her fall to the ground, her right arm was broken by the weight of her horse falling upon it. [United States Magazine and Democratic Review, V (Feb., 1839) 240.Thereafter she took part in underground activities until she was forced to flee, upon twenty-four hours' notice, and take up residence in France, under the protection of the Queen.

After arriving in Washington, she immediately set about preparing her memorial to Congress, and it was presented on the floor of the Senate eighteen days later. The Washington correspondent of a New York newspaper gave the following account for January 29, 1839:

The Senate went through the usual routine of business, and among the memorials presented was one from America Vespucci, presented by Mr. [Thomas Hart] Benton. The memorial was written in English and French by America Vespucci herself. She asks Congress, I believe, for a grant of land and for the rights of citizenship. The memorial was read by the Secretary of the Senate.Upon Mr. Benton's motion, the part of the memorial referring to a grant of lands was referred to the committee on Public Land and on Mr. Clay's motion, the second part referring to the right of citizenship, to the committee on the Judiciary. [N. Y. Morning Courier and Enquirer, Feb. 1, 1839, p. 2, col. 31]

Her petition was a long document, and from it I can quote for you only the two final paragraphs, as follows:

America Vespucci will make no demand on the American Government. Those who make demands are presumed to have rights to be established or justice to claim. She has neither. She knows that the Americans have been magnanimous towards all who have rendered services to the nation: that they have been generous towards all who have done a noble act for their country, and that they have, moreover, granted protection and even assistance to emigrants from other nations. There is but one Vespucius who has given his name to a quarter of the globe. Will the Americans do nothing for the descendant of Americus? She desires a country, she seeks a land that will receive her as a friend. She has a name: that is all her inheritance, all her fortune. May this hospitable nation grant her a corner of that land in which it is so rich, and may the title of citizen be bestowed upon the poor emigrant!If Americus Vespucius were now alive the Americans would rush in crowds to offer him honors and rewards. In the nineteenth century will this civilized nation forget that in the veins of his descendant flows the same blood?

America Vespucci collected all her little fortune in order to reach this country: now, she desires only to make known her position to the Congress of this great nation, feeling confident that the Americans will never abandon her.

She will not ask, having no other claim than that of bearing the name of America, but she will receive a gift from the nation by which she hopes not to be regarded as a stranger. That will not humiliate her. Such an act of generosity will console her feelings, honor her name, flatter her family, and even her country. The gifts of a nation always honor those who receive them. When the world shall know that the American nation has done an act of generosity in favor of the descendant of Vespucius, will not the approbation of all mankind be a glorious recompense? And true gratitude will remain in the heart of America Vespucci. [United States Magazine and Democratic Review, (Feb., 1839), 240]

While her memorial was under consideration in the committees, much discussion, pro and con, took place both in Washington and over the country. One feature was a lampoon sent to a New York City newspaper and widely printed over the country. It purported to be from a descendant of Hendrick Hudson and was modeled closely on Ameriga's memorial. Its text began as follows:

Washington, 1st February, 1839 An illustrious stranger has just arrived at this Metropolis. Her name is Grietje Truitje Hudzoon, and she is a descendant, in a straight line, of the celebrated navigator, Hendrick Hudson, the European discoverer of your far famed island [Manhattan], and who gave his name to the noble river which washes your shores- the honour not having been filched from him by a ship-mate. The object of her visit is, I understand, to ask of Congress a corner (een hackje! she calls it) of land, and the rights of citizenship, or in her own words, of Burgher Recht. She has drawn up in her own language, a memorial-rather prolix, to be sure-in which, after tracing her genealogy, she details the circumstances under which she quitted the Voderland. To liberal principles, she is, of course, a martyr— her ancestor having imbibed their spirit with the first breath of air he inhaled, that came from our shores, and handed it down as a sacred heirloom to all his posterity. The sufferings she endured in the cause of liberty, as well as those which were, by her account, inflicted on her, while passing through England on her way hither, from the combined dangers of steamships and rail-roads, are depicted by her in a most affecting manner. [N.Y. Morning Courier and Enquirer. Feb. 5, 1839, p. 2, col. 1]

After further reportage the satirist concluded with this account of her reception:

Majuff vrouwe Hudzoon, as you may suppose, attracts considerable attention here. The President, and the Honorable the Secretary of the Navy, are unwearied in their attentions to her; the former, it is even said, has gone so far as to offer her apartments in the White House, which she immediately however declined, on hearing he was a widower.God bewaar ons! Neen! she cried out— myn Kakakter!

Adam Ridabock

Early in March the committee that considered Ameriga's memorial brought in their report, and it was very respectful of her as a person. Their report began as follows:

A descendant of Americus is now here: a young, interesting, dignified, accomplished lady, with a mind and of the highest intellectual culture, and a heart beating with all our own enthusiasm in the cause of American and human liberty. She feels that the name she bears is a prouder title than any that earthly monarchs can bestow, and she comes here asking of us a small corner of American soil where she may pass the remainder of her days in this the land of her adoption. She comes here as an exile, separated forever from her family and friends, a stranger, without a country and without a home, expelled from her native Italy for the avowal and maintenance of opinions favorable to free institutions, and for the ardent desire for the establishment of her country's freedom. That she is indeed worthy of the name of America; that her heart is indeed imbued with American principles and a fervent love of human liberty, is proved, in her case, by toils, and perils, and sacrifices, worthy of the proudest days of antiquity, when the Roman and the Spartan matron were ever ready to surrender life itself in their country's service. [Niles' National Register (Baltimore), LVI (March 16, 1839), 41.]

The committee report has a special interest to students of onomastics, for it lauded America's name in the following words:

The American people ... feel and glory with us in the name of America. Throughout our wide extended country, among all classes, this feeling is universal: and in the humblest cottage the poorest American feels that this name, the name of his beloved country, is a prouder title than any that adorns the monarch's brow, and that, if he has no other property, this name, with all its great and glorious associations with the past, and hope for the future, is an all sufficient heritage to transmit to his children. (Ibid., p. 41]

That passage has special point because just at that time there was much discussion about changing the name of the country. Washington Irving had suggested that Alleghania or Appalachia would be better, and traditionalists were already mounting their opposition.

In spite of the kind words to Signora Vespucci, the committee felt obliged to refuse to accede to her requests, on legal grounds. It was not within the power of Congress, they felt, to cede any part of the public domain to one who had performed no personal service.

Their substitute suggestion was that a national subscription should be established, and that the gratitude of the American people would be enough to provide her with a home and support. The sergeant-at-arms of the Senate was designated to take in the contributions, which were received from many Senators from all parts of the Union, from Congressmen, from members of the Supreme Court, and from generous citizens. They enabled the Signora to travel widely over the country, presenting her case.

She was kindly received in many quarters; and even in England the denial of a grant to her was used as a club with which to belabor America. A London paper, the Age, declared itself as follows:

What a dirty souled confederation of blackguards these scoundrel Americans are. Swindlers in commerce, pirates, murderers, robbers, under the plea of universal liberty, whenever it suits their turn. What could poor Vespucci expect from the reprobate robbers of the universe? [London Age, as reprinted in the Boston Morning Post, May 17, 1839, p. 2, col. 2.]

Alas, the national subscription did not last long, so Ameriga returned to Paris to live with her sister. The American election of 1840, however, brought about a drastic change of direction, with the Jacksonians cast out of office. Friends of Ameriga sent word to her that her petition would stand a better chance with the new administration, and she returned in 1841, hoping for favorable action.

But reports began to trickle back from Europe that she had succumbed to the immoralities of the corrupt courts of Europe. The American puritanical outlook was such that the public spurned her, and she was left in desperate straits.

Still a very attractive woman, she became the mistress of America's most notorious roué, known as "Prince John," the son of the former President Martin Van Buren. After he took her as his sexual companion to the famous resort of White Sulphur Springs, she became a complete social outcast to the respectable families of the country. She continued to travel with him, putting him to bed dead drunk night after night as he descended further into alcoholism.

Another complication arose when reports came back from her family in Florence, who prided themselves on their respectability. The American consul at Genoa was Charles Edwards Lester, a well-known author of popular biographies. When gathering material about the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, he became friendly with the contemporary family in Florence, and found that they were bitter in their condemnation of the errant member in America.

Lester found that they denied her stories of heroism and regarded her as a headstrong, unmanageable girl who had deceived them and disgraced them. They claimed that they had gathered their few resources together and sent her first to Brazil, where she presented her petition to the government and was turned down. They felt, as Lester reported, that "by her dissolute life and barefaced deceptions, she blasted the prospects of her family, perhaps for ever!" [Lester's letter of February, 1845, in his book, The Artist, the Merchant, and the Statesman (N.Y., 1845), 11, 9]

They themselves wanted to petition Congress just as Ameriga had done, and the consul helped them to frame their document. They secured an effusive endorsement from the Grand Duke of Tuscany, dated April 8, 1845, and their petition, entitled

To the Generous

American Congress

was soon afterwards submitted to Congress. Its concluding paragraph read as follows:

The remarkable political events which have of late years convulsed Europe, and destroyed the estates of so many ancient families, have also wrecked the fortunes of the Vespucci race. They are at present reduced to poverty, though they yet hope for better fortune, through the generosity of the great American people.

Signed, Amerigo Vespucci

Eliza Vespucci

Teresa Vespucci

[Charles Edwards Lester, The Life and Voyages of Americus Vespucius, (N.Y., 1846), p. 418.]

Let us return now to the unfortunate Ameriga Vespucci. Her later history became suffused with legend and unsubstantiated stories as fanciful as those she had once told about herself. These stories circulate in the northern counties of New York, for she settled for nearly twenty years in the town of Ogdensburg, overlooking the St. Lawrence River.

Hardest to believe is the story of how she got to Ogdensburg; but it is told for truth by Carl Carmer in his Listen for a Lonesome Drum (N.Y ., 1936), pp. 358-64, and by several other local historians of the North Country. It is said that she was traveling with her "Prince John" when he came to the area to buy some land for a client. At the little village of Evans Mills, near Watertown, young Van Buren got into a poker game with a very wealthy landowner of the region. Prince John lost all of his money, together with that of his client, and as his final wager he bet the services of his mistress Ameriga, and lost that bet too.

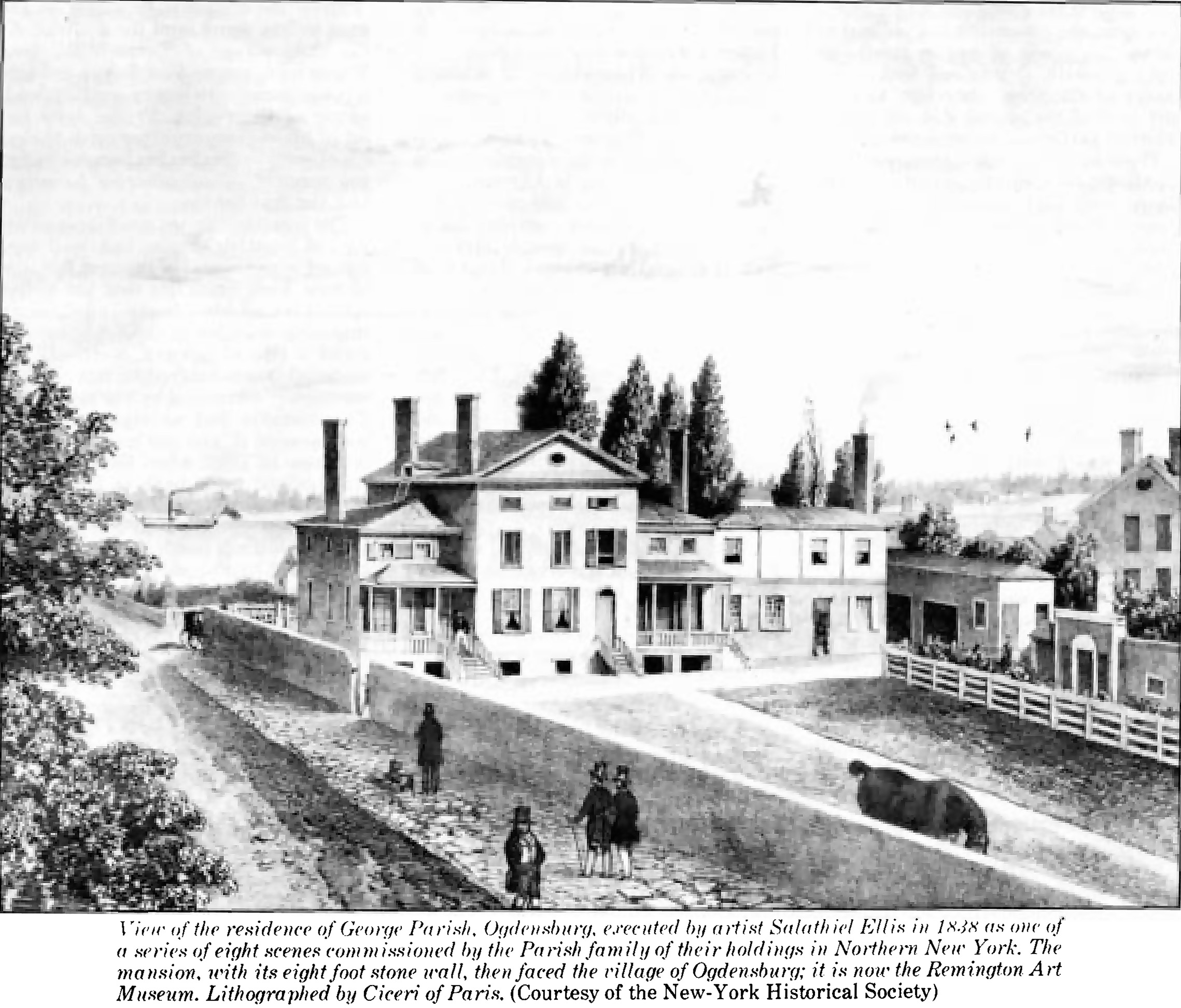

The wealthy winner was George Parish, of Scottish origin, but well connected with several of the best families of New York State. He took her to live with him as his "fancy lady" in an imposing mansion in Ogdensburg. She lived a life of luxury, with all her material wants catered to; but she was completely ostracized by her neighbors.

The mansion had an eight-foot stone wall around it, and she lived within its confines. In 1859, when George Parish was obliged to go back to Europe, he settled an annuity on her for life, and she herself returned to Paris, where she lived till her death in 1866.

It is believed by some that a popular song, "A Bird in a Gilded Cage," was inspired by her situation. Do its words apply to her? This is the chorus:

She's only a bird in a gilded cage,

A beautiful sight to see.

You may think she's happy and free from care,

She's not though she seems to be,

'Tis sad when you think of her wasted life,

For youth cannot mate with age,

And her beauty was sold, For an old man's gold,

She's a bird in a gilded cage.

[Sheet music, cop. 1900, words by Arthur J. Lamb, music by Harry von Tilzer.]

But the song was not composed until 1900, thirty-four years after her death, and it seems to me unlikely that there is any true historical connection.

The story of Ameriga Vespucci is a sad one, and she deserves our compassion. A lady of overwhelming charm and dazzling accomplishment, with an illustrious background in Tuscan history, was defeated by the lack of opportunities for women in her era. She is remembered now chiefly as what was then called a "kept woman." Yet she might, in other circumstances, have become a strong leader in some avenue of American culture.

About the Author

Dr. Allen Walker Read is ProfessorEmeritus of English at Columbia

University. He has produced many

books and articles on the study of

language, naming practices and folklore,

with such a variety of topics as

graffiti and proverbs.

America's Ingratitude for Its Naming: The Tribulations of Signora Vespucci

July 1983,

by Allen Walker Read

The St Lawrence County Historical Association Quarterly Volume XXVIII, Number 3