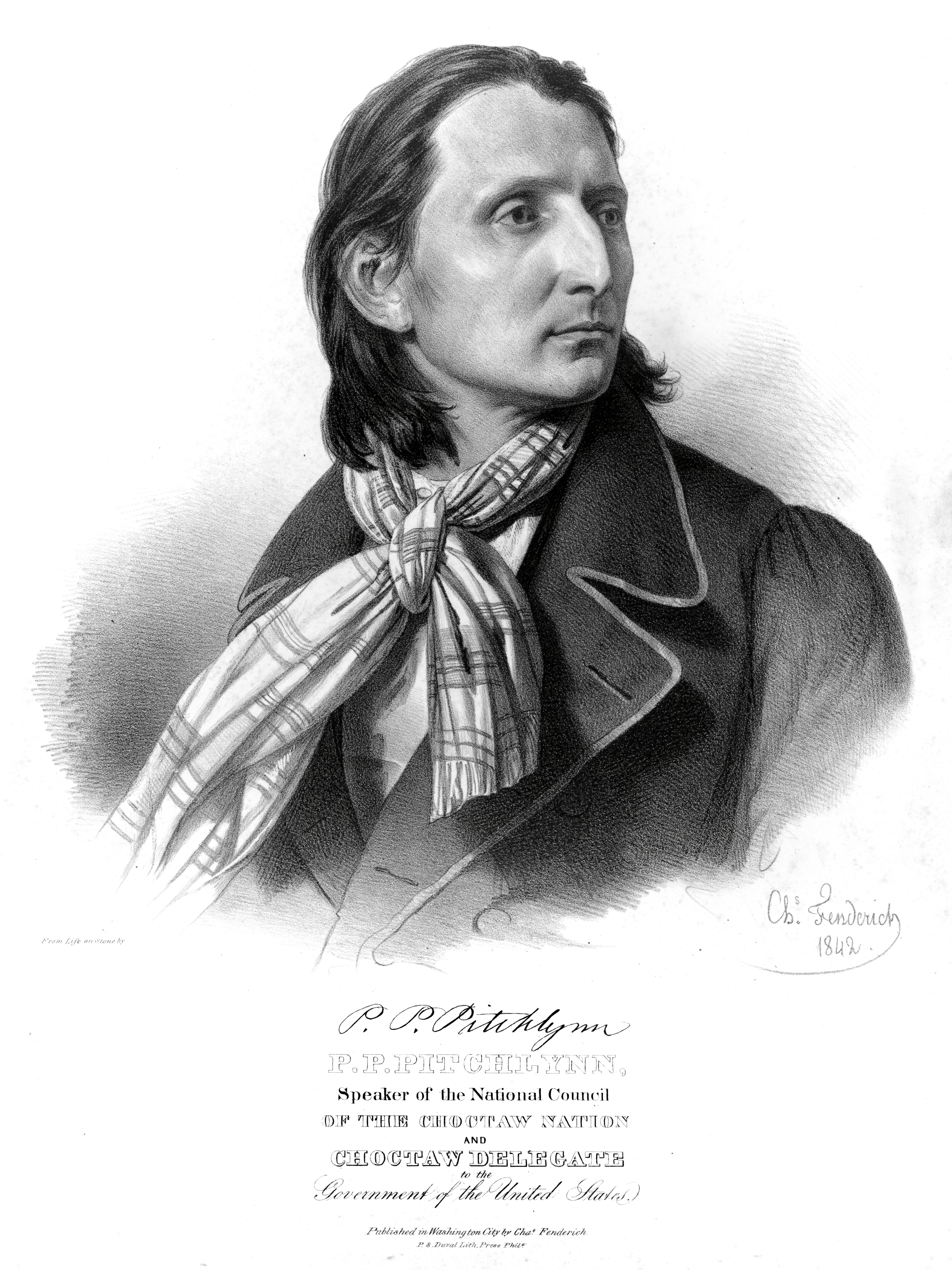

Peter Pitchlynn,

Chief of the Choctaws.

by Charles Lanman

The Atlantic monthly. / Volume 25, Issue 150, April 1870

When Mr. Charles Dickens first visited this country, he met upon a steamboat on the Ohio River a noted Choctaw chief, with whom he had the pleasure of a long conversation. In the “American Notes” we find an agreeable account of this interview, in which the Indian is described as a remarkably handsome man, and, with his black hair, aquiline nose, broad cheek-bones, sunburnt complexion, and bright, dark, and piercing eye, as stately and complete a gentleman of Natures making as the author ever beheld. That man was Peter P. Pitchlynn. Of all the Indian tribes which acknowledge the protecting care of the American government, there are none that command more respect than the Choctaws, and among their leading men there is not one more deserving of notice by the public at large than the subject of this paper. Merely as a romantic story, the leading incidents of his life cannot but be read with interest, and as a contribution to American history, obtained from the man himself, they are worthy of being recorded.

His father was a white man of a fighting stock, noted for his bravery and forest exploits, and an interpreter under commission from General Washington, while his mother was a Choctaw. He was born in the Indian town of Hush-ook-wa, now Noxabee County, in the State of Mississippi, January 30, 1806. The first duties he performed were those of a cowboy, but when old enough to bend a bow or hold a rifle to his shoulder, be became a hunter. In the councils of his nation he sometimes made his appearance as a looker-on, and once, when a member of the tribe who had been partially educated in New England was seen to write a letter to President Monroe, Pitchlynn resolved that he would himself become a scholar. The school nearest to his fathers log-cabin was at that time two hundred miles off among the hills of Tennessee, and to that he was dispatched after the usual manner of such important undertakings. As the only Indian-boy in this school, he was talked about and laughed at, and within the first week of his admission be found it necessary to give the “bully” of the school a severe thrashing. At the end of the first quarter he returned to his home in Mississippi, where be found his people negotiating a treaty with the general government; on which occasion he made himself notorious by refusing to shake the hand of Andrew Jackson, the negotiator, because in his boyish wisdom he considered the treaty an imposition upon the Choctaws. Nor did he ever change his opinion on that score. His second step in the path of education was taken at the Academy of Columbia, in Tennessee, and he graduated at the University of Nashville. Of this institution General Jackson was a trustee, and on recognizing young Pitchlynn, during an official visit to the college, he remembered the demonstration which the boy had made on their first meeting, and by treating him with kindness changed the old feeling of animosity to one of warm personal friendship, which lasted until the death of the famous Tennesseean.

On his return to Mississippi our hero settled upon a prairie to which his name was afterwards given, and became a farmer, but amused himself by an occasional hunt for the black bear. He erected a comfortable log-cabin, and, having won a faithful heart, he caused his marriage ceremony to be performed in public, and according to the teachings of Christianity, the Rev. C. Kingsbury being the officiating missionary, a man long endeared to the Southern Indians, and known as “Father Kingsbury”. As Pitchlynn was the first man among his people to set so worthy an example, we must award to him the credit of having given to polygamy its death - blow in the Choctaw nation, where it had existed from the earliest times.

Another reform which young Pitchlynn had the privilege and sagacity to promote among his people was that of temperance, which had for some years been advocated by an Indian named David Folsom. In a treaty made in 1820, an article had been introduced by the Choctaws themselves prohibiting the sale, by red men as well as white men, of spirituous liquors within their borders, but up to 1824 it remained a dead letter. During that year the Council of the Nation passed a law organizing a corps of light horse, to whom was assigned the duty of closing all the dram-shops that could be found carrying on their miserable traffic contrary to treaty stipulations. The command of this band was assigned to young Pitchlynn, who was thereafter recognized by the title of Captain. In one year from the time he undertook the difficult task of exterminating the traffic in liquor he had successfully accomplished it. As a reward for his services he was elected a member of the National Council, being the only young man ever thus honored. His first proposition, as a member of the Council, was for the establishment of a school; and, that the students might become familiar with the customs of the whites, it was decided that it should be located somewhere in their country.

The Choctaw Academy, thus founded near Georgetown, Kentucky, and supported by the funds of the nation, was for many years a monument of their advancing civilization. One of the most important and romantic incidents in Pitchlynn s career grew out of the policy, on the part of the general government, for removing the Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creeks from their old hunting-grounds to a new location west of the Mississippi River. At the request and expense of the United States, a delegation of Indians was appointed in 1828 to go upon an exploring and peace-making expedition into the Osage country, and of this party Pitchlynn was appointed the leader. He succeeded in making a lasting peace with the Osages, who had been the enemies of the Choctaws from time immemorial.

The delegation consisting of six persons, two from each of the three tribes interested, was absent from home about six months. The first town at which they stopped was Memphis; their next halt was at St. Louis, where they were supplied with necessaries by the Indian superintendent; and their last was Independence, which was then a place of a dozen log-cabins, and here the party received special civilities from a son of Daniel Boone. On leaving Independence the members of the delegation, all well mounted, were joined by an Indian agent, and their first camp on the broad prairie-land was pitched in the vicinity of a Shawnee village. This tribe had never come in conflict with the Choctaws (though the former took the side of Great Britain in the war of 1812), and, according to custom, a council was convened and pledges of friendship were renewed by an exchange of wampum and the delivery of speeches.

After these ceremonies, a grand feast took place at a neighboring village on the following day; and then the expedition continued its march towards the Osage country. For a time their course lay along the famous Santa Fe trail, and then, turning to the southwest, they journeyed over a beautiful country of rolling prairies skirted with timber, until they came to an Osage village, on a bluff of the Osage River. The delegation came to a halt within a short distance of the village, but for several days the Osages showed signs of their original enmity, and refused to meet the strangers in council; and as it was well known that several Osages had recently been killed by a wandering band of Choctaws, the probability of hostilities and an attempted surprise was quite apparent. The delegation, however, proposed a treaty of peace, and after a long delay the Osages agreed to meet them in general council; when Captain Pitchlynn stated that he and his party, the first Choctaws who had ever met the Osages with peaceful intentions, had traveled over two thousand miles by the advice of the United States government, in order to propose to the Osages a treaty of perpetual peace. To this an orator of the Osages made a defiant and unfriendly reply, and the delegation at a second council changed their tone.

Captain Pitchlynn, as before, was their only speaker. After casting a defiant look upon Bel Oiseau, the Osage orator, as well as upon the other Osages present, he proceeded in these words:

“After what the Osage warrior said to us yesterday, we find it very hard to restrain our ancient animosity. You inform us that by your laws it is your duty to strike down all who are not Osage Indians. We have no such law. But we have a law which tells us that we must always strike down an Osage when we meet him. I know not what war-paths you may have followed west of the Big River, hut I very well know that the smoke of our council-fires you have never seen, and we live on the other side of the Big River. Our soil has never been tracked by an Osage, excepting when he was a prisoner. I will not, like you, speak boastingly of the many war-paths we have been up on. I am in earnest, and can only say that our last war-path, if you will have it so, has brought us to the Osage country, and to this village. Our warriors at home would very well like to obtain a few hundred of your black locks, for it is by such trophies that they obtain their names. I mention these things to prove that we have some ancient laws as well as you, and that us, too, were made to fight. Adhere to the laws of your fathers, refusing the offer for peace that we have made, and you must bear the consequences. We are a little band now before you, but we are not afraid to speak our minds. Our contemplated removal from our old country to the sources of the Arkansas and Red Rivers will bring us within two hundred miles of your nation; and when that removal takes place, we will not finish building our cabins before you shall hear the whoop of the Choctaws and the crack of their rifles. Your warriors will then fall, and your wives and children shall be taken into captivity; and this work will go on until the Osage nation is entirely forgotten. You may not believe me, but our numbers justify the assertion, and it is time that the Indian race should begin a new kind of life. You say you will not receive the white paper of our father, the President; and we now tell you that we take back all that we said yesterday about a treaty of peace. A proposition for peace, if we are to have it, must now come from the Osages.”

This speech had the intended effect; the next day negotiations were opened by the Osages; peace was declared, and a universal shaking of hands succeeded. A grand feast next followed, and the entire Osage village, during the succeeding night, presented as joyous and boisterous an appearance as jerked buffalo-meat and water could inspire. Speeches furnished a large part of the entertainment, and to Captain Pitchlynn was awarded the honor of delivering the closing oration. He told the Osages that his people had adopted the customs of civilization, and were already reaping much benefit therefrom. They encouraged mission aries, established schools, and devoted attention to the pursuits of agriculture and the mechanic arts. He advised the Osages to do the same; to give up war as an amusement, and the chase as a sole dependence for food, and then they would become a happy and prosperous people. This was their only means of preservation from the grasping habits of the white man. If they would strive for civilization, the American government would treat them with greater kindness, and, though they might throw away their eagle-feathers, and live in permanent cabins, there was no danger of losing their identity or name. At the end of these prolonged festivities, Bel Oiseau and a party of warriors selected for the purpose escorted the delegation to the borders of the Osage country, a distance of one hundred and fifty miles, During the several nights which they spent together before parting Bel Oiseau was the chief talker, and he did much to entertain the whole party, while seated around their camp-fires, by relating what adventures and traditions he could remember. These he confused with facts of aboriginal history. He claimed that his people were descended from a beaver, and that the Osage hunters never killed that animal from fear of killing one of their own kindred. He boasted that if his tribe was not as large as many others, it had always contained the largest and handsomest men in the world; that their horses were finer than those owned by the Pawnees and the Comanches; that they preferred buffalo-meat for food to the fancy things which they used in the settlements; that the buffalo-robe suited them better than the red blanket; the bow and arrows were better than the rifle or gun; and he thought their Great Spirit was a better friend to them than the Great Spirit of the white man, who allowed his children to ruin themselves by drinking the firewater.

In returning to their own homes the Choctaws pursued a southern course, passed down the Canadian River, the agent leaving them at a point near Fort Gibson, and so continuing along the valley of the Red River; and, as before stated, after an absence of several months, they all reached their cabins in safety. They had some severe skirmishes with the Comanche Indians, and two of the party got lost for a time while hunting buffaloes and bears. Captain Pitchlynn picked up in one of the frontier cabins a bright little Indian-boy, belonging to no particular tribe as he said, carried him to Mississippi, and had him educated at the Choctaw Academy in Kentucky; and that boy is now one of the most eloquent and faithful preachers to be found in the Choctaw nation.

The expedition here sketched was the first step taken by the government towards accomplishing the removal of the Indian tribes eastward of the Mississippi River to a new and permanent home in the far West. The several tribes collected on the sources of the Arkansas and Red Rivers, and now living in a happy and progressive community, will probably number fifty thousand souls. Some eighteen thousand Cherokees and three thousand Seminoles have followed their example; so that while thirty-six hundred of the Southern Indians are said to be living at the present time in the country where they were born, the States of Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, seventy-one thousand have made themselves a new home westward of the Mississippi River.

Captain Pitchlynn was always an admirer of Henry Clay, and first made the acquaintance of the great statesman in 1840. The Choctaw was ascending, the Ohio in a steamboat, and at Maysville during the night the Kentuckian came on board, bound to Washington. On leaving his state-room at a very early hour Pitchlynn went into the cabin, where he saw two old farmers earnestly engaged in a talk about farming, and, drawing up a chair, he listened with great delight for more than an hour. Returning to his state-room he roused a traveling companion and told him what a great treat he had been enjoying, and added: “If that old farmer with an ugly face had only been educated for the law, he would have made one of the greatest men in this country.” That “old farmer” was Henry Clay, who expressed the greatest satisfaction at the compliment that had been paid him.

The steamboat was afterwards delayed at the mouth of the Kanawha, and, as was common on such occasions, the passengers held mock trials and improvised a debate on the relative happiness of single and married life. Mr. Clay consented to speak, and took the bachelor side of the question, while the duty of replying was assigned to the Indian. He was at first greatly bewildered, but recollecting that he had heard Methodist preachers relate their experiences on religious matters, he thought he would relate his own experiences of married life. He did this with minuteness and considerable gusto, laying particular stress upon the goodness of his wife and the different shades of feeling and sentiment which he had experienced; and after he had finished, the ladies present vied with Mr. Clay in applauding the talented and warm-hearted Indian.

When the war of the Rebellion commenced, in 1861, the subject of our sketch was in Washington, attending to public business for his people, but immediately hurried home in the hope of escaping the evils of the impending strife. Before leaving, however, he had an interview with President Lincoln and assured him of his desire to have the Choctaws pursue a neutral course, to which the President assented as the most proper one to adopt under the circumstances. But Pitchlynns heart was for the Union, and he made the further declaration, that, if the general government would protect them, his people would certainly espouse its cause. He then returned to the South-west, intending to lead the quiet life of a planter on his estate in the Choctaw country. But the white men of Arkansas and Texas had already worked upon the passions of the Choctaws, and on reaching home he found a large part of the nation already infected with the spirit of rebellion. He pleaded for the national government, and, at the hazard of his life, denounced the conduct of the Southern authorities. Many stories were circulated to increase the number of his enemies; among them was one that he had married a sister of President Lincoln, and another that the President had offered him four hundred thousand dollars to become an Abolitionist. He was sustained, however, by the best men in the nation, who made him colonel of a regiment of militia for home defense, and afterwards elected him Head Chief of the Choctaws; but all this did not prevent two or three of his children, as well as many others in the nation, from joining the Confederate Army. He himself remained a Union man during the entire war. Not only had many local positions of honor been conferred upon him in times past, but he had long been looked upon by all the Choctaws as their principal teacher in religious and educational matters, as their philosopher and faithful friend, and also as the best man to represent their claims and interests as a delegate to Washington. He had under cultivation, just before the Rebellion, about six hundred acres of land, and owned over one hundred slaves; and though he annually raised good crops of cotton and corn, he found the market for them too far off, and was beginning to devote all his attention to the raising of cattle. His own stock and that of his neighbors was of course a prize for the Confederates, who took everything, and left the country almost desolate.

When the Emancipation Proclamation appeared, he acquiesced without a murmur, managing as well as he could in the reduced condition of his affairs; and after the war, he was again solicited to revisit Washington as a delegate, in which capacity he was assigned the charge of a claim for unpaid treaty money of several millions of dollars.

An address that he delivered as delegate before the President at the White House in 1855 was commented upon at the time as exceedingly touching and eloquent; and certain speeches that he made before Congressional committees in 1868, and especially an address that he delivered in 1869 before a delegation of Quakers, called to Washington by President Grant for consultation on our Indian affairs, placed him in the foremost rank of orators.

While it is true that the most populous single tribe of Indians now living in this country is that of the Cherokees, the Choctaws and Chickasaws, who form what is known as the Choctaw nation, outnumber the former by about live thousand, and they claim in the aggregate near twenty thousand souls. They both speak the same language, and have attained a higher degree of civilization than any other of the South rn tribes. The nation is divided into four districts, one of which is composed exclusively of Chickasaws; each district was formerly under one chief; hut now they are all ruled by a single chief or governor; and they have a National Legislative Council. They have an alphabet of their own, and are well supplied with schools and academies, with churches and benevolent institutions, and, until lately, had a daily press. They are the only tribe which has never, as a whole, been in hostile collision with, nor been subdued by, the United States. Have they never broken a promise or violated their plighted faith with the general government?

What certain individuals may have done during the late war ought not certainly to be charged against the nation at large. The Choctaws and Chickasaws claim for their territory, that it is as fertile and picturesque as could he desired. To speak in general terms, it forms the southeast quarter of what is called the Indian Territory. It is about two hundred miles long by one hundred and thirty wide, forming an elongated square; and while the Arkansas and Canadian Rivers bound it on the north, it joins the State of Arkansas on the east, and the Red River and Texas hound it on the south and west. These two nations, now living in alliance, consider themselves much more fortunate now than they were in the “old country”, the designation which they love to apply to Mississippi. Their form of government is similar in all particulars to that of the States of the Union.

While it is true that the Rebellion had a damaging effect upon their affairs, it cannot he long before they will be restored to their former prosperous condition. They adopted and supported before the war a system of what they called “neighborhood schools”, as well as seminaries, taught for the most part by ladies from the New England States, and intended to afford the children a primary course of instruction and fit them for the colleges and seminaries in the States, to which many pupils have hitherto been annually sent. The prime mover in all these educational enterprises was Colonel Pitchlynn, and it is now one of the leading desires of his heart that the good lady teachers, who were driven off by the war would either return themselves, or that others like them might be sent out from New England. In his opinion, these teachers were the best civilizers of the Choctaw nation. To New England clergymen also are the Choctaws indebted for their best translations of the Scriptures and other religious books. Their school system, which was eminently prosperous until interfered with by the Rebellion, was founded in 1842. Up to that date the general government undertook to educate that people, and the funds set aside for the purpose were used by designing men for their own benefit. Pitchlynn well knew that he would have to fight an unscrupulous opposition, but he resolved to make an effort to have the school fund transferred from the United States to the Choctaws. After many delays, he obtained an interview with John C. Spencer, then Secretary of War, and was permitted to tell his story. The Secretary listened attentively, was much pleased, and told the chief he should have an interview with the President, John Tyler. The speech which he then delivered in the White House and before the Cabinet was pronounced wonderful by those who heard it. It completely converted the President, who gave immediate orders that Pitchlynns suggestions should all be carried out. The Secretary fully co-operated; and before the clerks of the Indian Office quitted their desks that night the necessary papers had been prepared, signed, sealed and duly delivered.

At the commencement of the Rebellion the number of slaves in the Choctaw nation was estimated at three thousand; and these, in the capacity of freedmen, are now waiting for the general government to keep its promises in regard to their welfare. By a treaty which was ratified in i866 they were to be adopted by the Choctaws and Chickasaws, and those tribes were to receive a bonus of three hundred thousand dollars; if this stipulation should fail, the government was to remove them to some public lands, where they might found a colony; and as the Indians have thus far failed to adopt the freedmen, the latter are patiently waiting for the government to keep its solemn promises. These unfortunate people are said to be more intelligent and self-reliant than many of their race in the Southern States, and it certainly seems a pity that they should continue in their present unsatisfactory and disorganized condition. It is due to Colonel Pitchlynn to state, that from the beginning he has advocated the adoption of the freedmen. Ever since the removal of the Choctaws and Chickasaws to their Western territory, missionaries and school teachers have labored among them with great faithfulness, and the denominations which have chiefly participated in this good work are the Baptist, the Methodists, and the Cumberland and Old-School Presbyterians. Upon the whole, the cause of temperance has fared as well with them as with any of the fully civilized people of the Atlantic States. In certain parts of the interior alcoholic drinks are seldom if ever seen, but this cannot be said of those parts bordering on Arkansas and Texas. No white man is allowed citizenship among them unless he marries a Choctaw. Some years ago they concluded to adopt one man, but during the next winter no less than five hundred petitions were sent in for the same boon, which was not granted.

That there has always been a want of harmony among this people on moral as well as political questions cannot be denied, and the fact may be attributed to a few influential families, whom unprofitable jealousies and a party spirit are kept up, to the disadvantage of the masses. If there is anything among them which might be called aristocracy, it consists more in feeling than in outward circumstances; for all the people live alike in plain hut comfortable log-cabins, and are content with a simple manner of life. They have a goodly number of really intellectual men; but it is undoubtedly true that, so far as the higher qualities are concerned, the particular man of whom we have been writing is without a peer.

To be the leading intellect among such a people is, of course, no ordinary honor, and Colonel Pitchlynn has always cherished with affectionate pride their history and romantic traditions. He is, indeed, the poet of his people and he has communicated to the writer many Choctaw legends, stored up in his retentive memory, which have never appeared in print, and which, but for Pitchlynns appreciation of their beauty, would scarcely have been repeated to a white man.

According to one of these traditions, the Choctaw race came from the bosom of a magnificent sea, supposed to he the Gulf of Mexico. Even when they first made their appearance upon the earth, they were so numerous as to cover the sloping and sandy shore, far as the eye could reach, and for a long time they traveled upon the sands before they could find a place suited to their wants. The name of their principal chief or prophet was Chah-tah, and he was a man of great age and wisdom. For many moons their bodies were strengthened by pleasant breezes and their hearts gladdened by perpetual summer. In process of time, however, the multitude was visited by sickness, and the dead bodies of old women and little children one after another were left upon the shore. Then the heart of the prophet became troubled, and, planting a long staff which he carried in his hand, and which was endowed with the powers of an oracle, he told his people that from the spot designated they must turn their faces towards the unknown wilderness. But before entering upon this part of their journey he specified a certain day for starting, and told them that they were at liberty, in the meantime, to enjoy themselves by feasting and dancing and performing their national rites.

It was now early morning and the hour appointed for starting. Heavy clouds and flying mists rested upon the sea, but the beautiful waves melted upon the shore as joyfully as ever before. The staff which the prophet planted was found leaning towards the point in the north, and in that direction did the multitude take up their line of march. Their journey lay across streams, over hills, through tangled forests, and over immense prairies. They now arrived in an entirely new country; they planted the magic staff every night with the utmost care, and arose in the morning with eagerness to ascertain the direction in which it leaned. And thus had they traveled many days when they found themselves upon the margin of an O-kee-na-chitto, or great highway of water, the Mississippi River. Here they pitched their tents, and, having again planted the straw lay down to sleep. When morning came, the oracle told them that they must cross the mighty river before them. They built themselves rafts and reached the opposite shore in safety. They now found themselves in a country of rare beauty, where the trees were so high as almost to touch the clouds, and where game of all kinds and the sweetest of fruits were found in great abundance. The flowers of this land were more brilliant than any they had ever seen, and so large as often to shield them from the sunlight of noon. With the climate of the land they were delighted, and the air they breathed seemed to fill their bodies with new strength. So pleased were they with all they saw, that they built mounds in all the more beautiful valleys through which they passed, so that the Master of Life might know they were not an ungrateful people. In this country they resolved to remain, and here they established their government, and in due time made the great mound of Nun-i-wai-ya, near the head-waters of what is now known as Pearl River in Mississippi.

Time passed on, and the Choctaw nation became so powerful that its hunting-grounds extended even to the sky. Troubles now arose among the younger warriors and hunters of the nation, until it came to pass that they abandoned the cabins of their fathers, and settled in distant regions of the earth. Thus, from the body of the Choctaw nation have sprung those other nations which are known as the Chickasaws, the Cherokees, the Creeks or Muscogees, the Shawnees, and the Delawares. And in process of time the Choctaws founded a great city, wherein their aged men might spend their days in peace; and, because they loved those of their people who had long before departed into distant regions, they called this city Yazoo, the meaning of which is, Home of the people who are gone

Another legend, entitled The Overflowing Waters, is as follows. The world was in its prime. The tiny streams among the hills and mountains shouted with joy, and the broad rivers wound their wonted course along the peaceful valleys. The moon and stars had long made the night skies beautiful, and guided the hunter through the wilderness. The sun, which the red man calls the glory of summer-time, had never failed to appear. Many generations of men lived and passed away. But in process of time the aspect of the world became changed. Brother quarreled with brother, and cruel wars frequently covered the earth with blood. The Great Spirit saw all these and was displeased. A terrible wind swept over the wilderness, and the Ok-la-ho-ma, or red people, knew that they had done wrong, but they lived as if they did not care. Finally, a stranger prophet made his appearance among them, and proclaimed in every village the news that the human race was to be destroyed. None believed his words, and the moons of summer again came and disappeared. It was now the autumn of the year. Many cloudy days had occurred, and then a total darkness came upon the earth, and the sun seemed to have departed forever. It was very dark and very cold. Men lay down to sleep, hut were troubled with unhappy dreams. They arose when they thought it was time for the day to dawn, but only to see the sky covered with a darkness deeper than the heaviest cloud. The moon and stars had all disappeared, and there was constantly a dismal bellowing of thunder all round the sky. Men now believed that the sun would never return, and there was great consternation throughout the land. The great men of the Choctaw nation spoke despondently to their fellows, and sung their death-songs, but those songs were faintly heard in the gloom of the great night. Men visited each other by torchlight. The grains and fruits of the land became moldy, and the wild animals of the forest became tame, and gathered around the watch-fires of the Indians, entering even into the villages.

A louder peal of thunder than was ever before heard now echoed through the firmament, and a light was seen in the north. It was not the light of the sun, but a gleam of distant waters. They made a mighty roar, and, in billows like the mountains, they rolled over the earth. They swallowed up the entire human race, and destroyed everything which had made the earth beautiful. Only one human being was saved, and that was the mysterious prophet who had foretold the calamity. He had built a raft of sassafras-logs, and upon this he floated above the waters. A large black bird came and flew in circles above his head. He called upon it for help, but it shrieked aloud, and flew away and returned no more. A smaller bird, of a bluish color, with scarlet eyes and beak, now came hovering over the prophets head. He spoke to it, and asked if there were a spot of dry land in any part of the waste of waters. It fluttered its wings, uttered a wail, and flew directly towards that part of the sky where the newly horn sun was just sinking in the waves. A strong wind now arose, and the raft of the prophet was rapidly borne in that direction. The moon and stars again made their appearance, and the prophet landed upon a green island, where he encamped. Here he enjoyed a long and refreshing sleep, and when morning dawned, he found that the island was covered with every variety of animals, excepting the great Shakanli, or mammoth, which had been destroyed. Birds, too, he also found here in great abundance. He recognized the identical black bird which had abandoned him to his fate upon the waters, and, as it was a wicked bird and had sharp claws, he called it Fulluh-chitto,, or Bird of the Evil One. He also discovered, and with great joy, the bluish bird which had caused the wind to blow him upon the island, and because of its kindness to him and its beauty, he called it Puch-che-yon-sho-ba or the Soft-voiced Pigeon. The waters finally passed away; and in process of time that bird became a woman and the wife of the prophet, and from them all the people now living upon the earth were descended. And so ends the story of the overflowing waters, in which the reader must have noted the strong resemblance to the scriptural account of the Deluge.

The most poetical of Pitchlynns stories is that of The Unknown Woman, which is as follows. It was in the very far-off times, and two hunters were spending the night by their watch-fire in a bend of the river Alabama. The game and the fish were with every new moon becoming less abundant, and all they had to satisfy their hunger was the tough flesh of a black hawk. They were very tired, and as they reflected upon their condition, and thought of their hungry children, they were very unhappy, and talked despondently. But they roasted the bird before the fire, and tried to enjoy their repast. Hardly had they commenced eating, before they were startled by a singular noise resembling the cooing of a dove. Looking in one direction they saw nothing but the moon just rising above the thick woods on the opposite side of the river. Looking up and down the stream, they could see nothing but the sandy shores and the dark waters which were murmuring a low song. They turned their eyes in the quarter directly opposite the moon, and there discovered, standing upon the summit of a grassy mound, the form of a beautiful woman. They hastened to her side, when she told them she was very hungry, and thereupon they ran after their roasted hawk and gave it all into the hands of the woman. She barely tasted the proffered food, but told the hunters that their kindness had preserved her from suffering, and that she would not forget them when she returned to the happy grounds of her father, who was the Hosh-tal-li, or Great Spirit, of the Choctaws. She had one request to make, and this was, that when the next moon of midsummer should arrive they must visit the spot where she then stood. A pleasant breeze swept among the forest leaves, and the strange woman disappeared. The hunters were astonished, but they returned to their families, and kept all that they had seen and heard hidden in their hearts. Summer came, and they once more visited the mound on the banks of the Alabama. They found it covered with a plant whose leaves were like knives of the white man; and it yielded a delicious food, which has since been known among the Choctaws as the sweet toucka, or Indian maize.

Like the foregoing in spirit is this little story about the Hunter of the Sun. The Choctaws were always a grateful people, and once, after enjoying a rich harvest of the sweet maize, they held a national council, and their leading prophet descantedat great length upon the beauty of the earth, attributing the blessings they enjoyed to the sun. They knew that the great luminary came from the east, but none of them had ever found out what became of it when it passed beyond the mountains at the close of day. Is there not, said the prophet, among all my people a single warrior who will go upon a long journey and find out what becomes of the sun? Then it was that a young warrior named Ok-la-no-wa, or the traveler, arose and said, I will go and try to find out the sleeping-place of the sun, and if unsuccessful will never return. Of course, the saddest mourner that he left behind was the girl whom he loved, and to whom he had presented a belt of scarlet wampum. After many years the traveler returned to the region of his birth, but so many changes had taken place that he felt himself a stranger to the people. The only person who seemed to remember anything about his exploit was a very old woman, and although she was really the girl he had loved in his youth, she talked a great deal about the long-lost Ok-la-no-wa, and laughed at the idea as foolish that he and the old man present were the same. The old man spent the entire winter in telling the people about the wide prairies and high mountains he had crossed, about the strange men and animals that he had seen, and that when the sun went out of sight in the evening it always sank into a blue sea; but the old woman would not listen, and remained in her cabin, counting the wampum in her belt; and when spring came the old man died, and was buried in the mound of Nun-i-wai-ya, and before the end of the corn-planting moon the aged woman also died, and was buried by her loving friends by the side of Ok-la-no-wa in the mound of Nun-i-wai-ya. And when the Indians see the bright clouds gathering around the sun, they think of the hunter of the sun, and of the girl he loved, with her belt of scarlet wampum.

But in the way of a love legend the following account of the Nameless Choctaw is perhaps as good a specimen as the writer can submit; and with this he will conclude his chapter of Choctaw lore. There once lived in the royal Indian town of E-ya-sho (Yazoo) the only son of a war chief, who was famous for his handsome form and lofty bearing. The old men of the nation looked upon him with pride, and said that his courage was rare, and he was destined to be an eminent warrior. He was also an eloquent orator. But with all these qualities he was not allowed a seat in the councils of his nation, because he had not yet distinguished himself in war. The fame of baying slain an enemy he could not claim, nor had he even been fortunate enough to take a single prisoner. He was greatly beloved, and, as the name of his childhood had been abandoned, according to an ancient custom, and he had not yet won a name worthy of his ability, he was known among his kindred as the Nameless Choctaw. In the town of E-ya-sho there also once lived the most beautiful maiden of her tribe. She was the daughter of a hunter, and the promised wife of the Nameless Choctaw. They met often at the great dances, but, in accordance with Indian custom, she treated him as a stranger. They loved, and one thought alone entered their minds to cast a shadow. They knew that the laws of their nation were unalterable, and that she could not become his wife until he had won a name in war, though he could always place at the door of her lodge an abundance of game, and could deck her with the most beautiful wampum and feathers. It was now midsummer, and the evening hour. The lover had met his betrothed upon the summit of a hill covered with pines. From the centre of a neighboring plain rose the smoke of a large watch-fire, around which were dancing a party of four hundred warriors. They had planned an expedition against the distant Osages, and the present was the fourth and last night of the preparation ceremonies. Up to that evening the Nameless Choctaw had been the leader in the dances, and even now he was only temporarily absent, for he had stolen away for a parting interview with his beloved. They separated, and when morning came the Choctaw warriors were upon the war-path leading to the head-waters of the Arkansas. On that stream they found a cave, in which, because they were in a prairie-land, they secreted themselves. Two men were then selected as spies, one of whom, the Nameless Choctaw, was to reconnoiter in the west, and the other in the east. Night came, and the Indians in the cave were discovered by an Osage hunter, who had entered to escape the heavy dews. He at once hastened to the nearest camp, told his people what he had seen, and a party of Osage warriors hastened to the cave. At its mouth they built a fire, and before the dawn of day the entire Choctaw party had been smothered to death by the cunning of their enemies.

The Choctaw spy who journeyed to the east had witnessed the surprise and unhappy fate of his brother-warriors, and, soon returning to his own country, he called a council and revealed the sad intelligence. As to the fate of the nameless warrior who had journeyed towards the west, he felt certain that he too must have been overtaken and slain. Upon the heart of one this story fell with a heavy weight; and the promised wife of the lost Choctaw began to droop, and before the moon had passed away she died and was buried on the spot where she had parted with her lover.

But what became of the Nameless Choctaw? It was not true that he had been overtaken and slain. He was indeed discovered by the Osages, and far over the prairies and across the streams was he closely pursued. For many days and nights did the race continue, but the Choctaw finally made his escape. His course had been very winding, and when he came to a halt he was astonished to find that the sun rose in the wrong quarter of the heavens. Everything appeared to him wrong and out of order, and he became a forlorn and bewildered man. At last he found himself at the foot of a mountain which was covered with grass, and unlike any he had ever before seen. It so happened, however, at the close of a certain day, that he wandered into a wooded valley, and, having made a rude lodge and killed a swamp rabbit, he lighted a fire, and prepared himself for at least one quiet supper and a night of repose. Morning dawned, and he was still in trouble, but continued his wanderings. Many moons passed away; summer came, and he called upon the Great Spirit to make his pathway plain. He hunted the forests for a spotted deer, and having killed it, on a day when there was no wind he offered it as a sacrifice, and that night supped upon a portion of the animals flesh. His fire burnt brightly, and, though lonesome, his heart was at peace. But now he hears a footstep in an adjoining thicket! A moment more, and a snow white wolf of immense size is crouching at his feet, and licking his torn moccasins. “How came you in this strange country?” inquired the wolf; and the poor Indian told the story of his many troubles. The wolf took pity upon him, and said that he would conduct him in safety to the country of his kindred; and on the following morning they departed. Long, very long was the journey, and very crude and dangerous the streams which they had to cross. The wolf helped the Indian to kill game for their mutual support, and by the time that the moon for weeding corn had arrived the Choctaw had entered his native village again. This was on the anniversary of the day he had parted from his betrothed, and he now found his people mourning for her untimely death. Time and suffering had so changed the wanderer that his relatives and friends did not recognize him, and he did not make himself known. Often, however, he made them recount the story of her death, and many a wild song, to the astonishment of all, did he sing to the memory of the departed, whom he called by the name of Imma, or the idol of warriors. On a cloudless night he visited her grave, and at a moment when the Great Spirit cast a shadow upon the moon he fell upon the grave in grief and died. For three nights afterwards the inhabitants of the Choctaw village were alarmed by the continual howling of a wolf and when it ceased, the pine forest upon the hill where the lovers were resting in peace took up the mournful sound, and has continued it to the present time.

PDF Digitized by Google.