WHEN a site for the “Federal City” was under discussion, some statesmen, in whom the historic sense was strong, suggested Fredericksburg. Since then, research has revealed romantic adventures in that region more than fifty years anterior to its settlement by English people. There the first Christian shrine was built (1570) and its Spanish missionaries massacred; there Captain John Smith fought with the Rappahannocks (1608). It would have been historically as well as physically a picturesque place for the national capital. In the present paper, however, I must content myself with a moderate degree of antiquity.

In 1675 occurred the killing of Robert Hen and an Indian, both in the employ of a Burgess of Stafford County, which led to Colonel John Washington's siege of the Doegs, on the present site of Washington City, to their massacre while under a flag of truce, to reprisals, and to Bacon's Rebellion, whose significance has been recently shown in this magazine. In March, 1675, the Jamestown government ordered “one hundred and eleven men out of Glocester county to be garrisoned at one ffort or place of defence at or neare the ffalls of Rapahannock river, of which ffort Major Lawrence Smith to be captain or cheife comander.” The ammunition assigned for this was “ffower hundred and eighty pounds of powder and fforeteene hundred fforty three pounds of shot,” — much more than was distributed to either of the four other river forts by the same act. This was the beginning of Falmouth, now by bridges made a suburb of Fredericksburg. Falmouth may fairly claim to be the oldest town on the Rappahannock. Though its fort was but temporarily manned in 1675, Major Lawrence Smith recognized the advantages of the place ‐ then the head of navigation, and with a fine water power in its falls — and made certain proposals to the government, which were adopted in April, 1679. He was to mark out below the falls a piece of land one mile in length, and a quarter of a mile backward into the woods, and thereon build habitations for 250 men, of whom 50 were to be well armed and kept ready for action at tap of drum. Around this a larger district was defined, within which the Major and his 250 were to have “priviledges,” — to wit: three miles above and two below the fort, by four miles back from the river. Major Lawrence Smith, with two commissioners chosen by himself from the inhabitants, and six chosen by a majority of the 250, was empowered to hold a court within these limits — the usual appeals being allowed — to make such by-laws as a county might make, and administer them.* “Within the said ground,” continues the Act (Hening II.) “all which he (Smith) presumes and accompts to be his own land, noe person or persons to the number of two hundred and ffifty whome he shall seate or receive to dwell within the mile on the river, and quarter of a mile backwards as is before mentioned, shal be lyable to be arrested for any debt due by judgement, sealed bond, bill, note, booke debt or otherwaies, but shalbe free and acquitt from any arrest or suite of law for any matter or thing whatsoever except at the kings majesties suite, for the full space of twelve yeares, &c.” They are all free of taxes for fifteen years. But the district is not to be a refuge or asylum for fugitive servants, or slaves, or accused persons. This document is signed by Sir Henry Chicheley, governor; Matthew Kemp, speaker; and Robert Beverley, clerk of the Assembly, attests the copy.

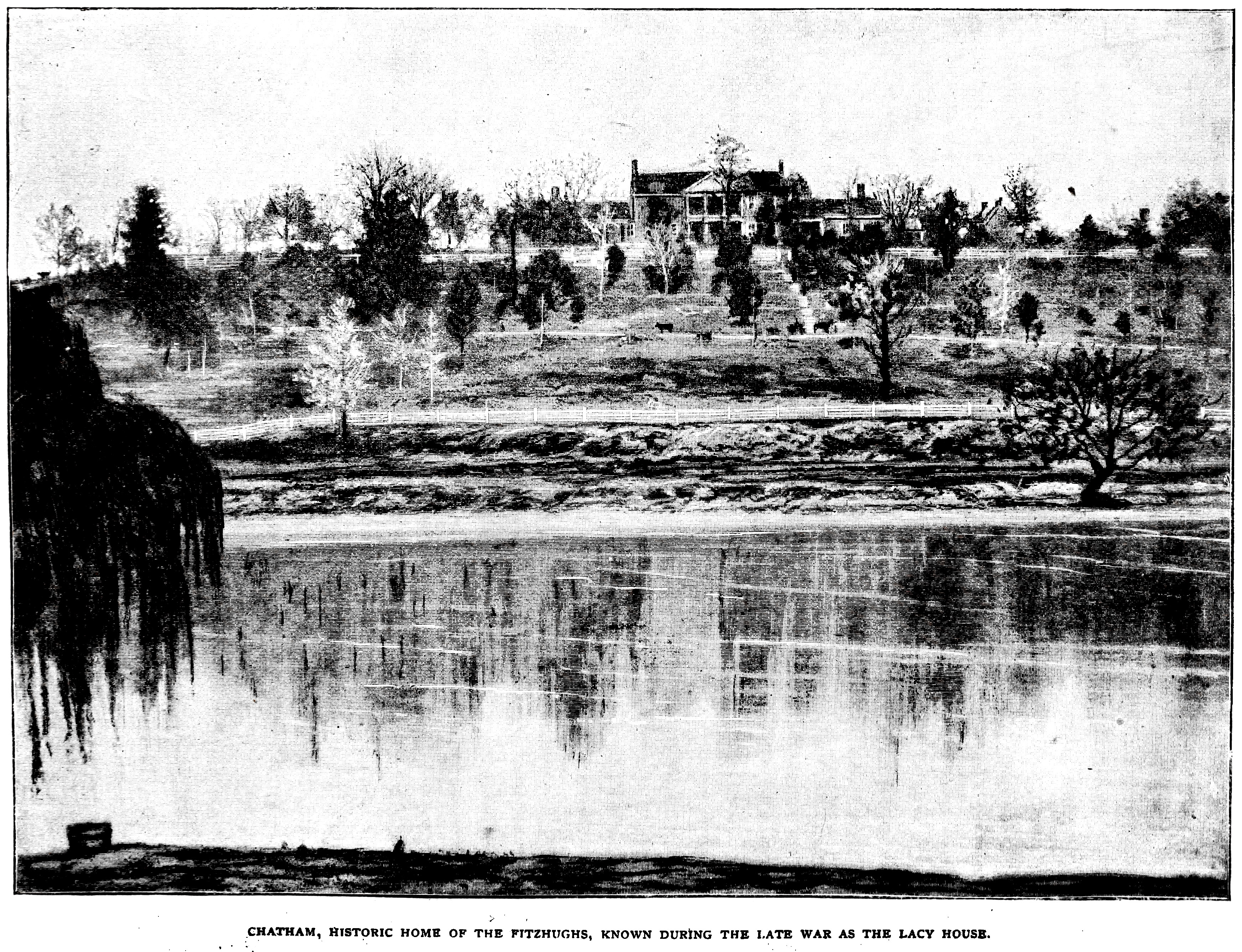

The site of this military district, of which Falmouth is the centre, is one of the most historical in the United States. Where Captain John Smith anchored his vessel and fought with Indians in 1608, another Captain Smith, sixty-eight years later, built a fort, and, three years after, a town. His empire included, possibly, the ground on which George Washington passed his boyhood, certainly Chatham, the headquarters of the Federal generals in the late war; while the old fort hill was used to bombard Fredericksburg in 1862. Not one stone or brick of the fort is left on another, but the terraces on the long hill back of the riverside houses still bear traces of ancient work.

The garrison regulations of the time were severe. A blasphemer, drunk or sober, must for every offense run the gauntlet through one hundred men, and, if willfully persistent in such offense, be bored through the tongue with a hot iron. The same for any soldier who shall deride the Bible or sacraments. After a third conviction for swearing or drunkenness, the offender must “ride the wooden horse half an hour with a musket tyed at each foote, and ask forgiveness at the next meeting for prayer or preaching.”

* This little princedom was then in old Rappahannock County (now extinct); in 1692, it became Richmond; in 1720, King George; in 1776, Stafford was extended to the river. Across the river Rappahannock County became Essex, in 1692, and Spottsylvania (in honor of the darling Governor Spottswood) in 1720. See picture of Chatham on page 190.

Non-attendance at prayer-meeting or preaching, every morning and evening, punished at the discretion of the commander.” If any offers to strike them (officers) with his hand, whether he hitt or misse, he shall loose his right hand.” Laziness in any service is punished with the wooden horse; and silence while marching is encouraged by “the penaltie to be laid neck and heels during the space of one hour for every such offence.” Nine offenses were punishable with death — most of them being still so punishable in time of war. The fort at Falmouth, built after a declaration of war against the Indians, passed under civil regulations when the town was built (1679), but certain military privileges remained, and, no doubt, some corresponding severities.

The fort and settlement near the falls are not again mentioned in the acts of assembly, so far as preserved, and this may have led the late George Fitzhugh to suppose that Major Lawrence Smith's settlement was “abortive.” But any one familiar with Falmouth will feel certain that a considerable number of its houses are quite two hundred years old. Probably we may find an explanation of the silence of the records in the following paragraph of an Act (April, 1692,) dividing Rappahannock County, which till then lay on both sides of the river. The northern side was now named Richmond; the southern, Essex; and it is enacted “by their Majesties” etc., that “the records belonging to the county court of Rappahanoc before this division be kept in Essex county, that belonging wholly to their Majesties and the other to the proprietors of the Northern Neck.” It would require as many pages as I can here give sentences to report the causes and consequences of this severance of the country between the Rappahannock and Potomac from the rest of Virginia. Its presentation as a private estate to Lord Culpeper was the beginning of a reign of terror which did not end until the ancient regime on the Rappahannock was broken up. The gentry were in panic. Their tobacco —their wealth and currency— had been subjected to ruinous levies and restrictions; their servants and slaves were becoming burdens. They now expected their land titles to be taken away. It did not so prove, but distrust broke the link of loyalty between the Rappahannock and Jamestown. Amid the dismays of the time came rumors that the king, with alliance of Indians and negroes, meant to crush Protestantism. This brought forth a fiery clergyman of the Established Church, John Waugh, of Stafford County, whose voice rang through the valley until the people took up arms. This excitement ended in 1689, when William and Mary were proclaimed “Lord and Lady of Virginia,” but the old baronial life on the Rappahannock could not be fully recovered. Alarms environed the larger and lonelier plantations. The white retainers had been dismissed to become “poor whites;” their masters were beginning to look about for some means of earning livelihood by means less precarious than tobacco. They began to gather near villages, to trade, to study professions. When that untitled representative of the English middle class, Alexander Spottswood, came to Virginia (1710), he found a people of his own class, prepared to work. Colonel John Washington, once a hunted royalist, had hunted Indians; his grandson, Augustine, was busy with Principio iron-furnace, one of the four which were operating on the Rappahannock when George Washington was born.* All this was the work of “Tubal Cain”. Spottswood, and his Germans in one sense; in another, it was the result of the long series of suicidal acts of English despots, large and little, by which the cavaliers were largely severed from their estates; in yet another, it was due to the energy characteristic of gentlemen often supposed indolent, but who in all their affairs have always displayed an almost painful eagerness and activity —whether hunting, fighting, or working. It was these dislocated elements — rich and poor — of a perishing regime, which were presently represented in the two towns at the head of navigation on the Rappahannock — Fredericksburg and Falmouth. These towns were founded legally after the region had already become flourishing, by the same act — February, 1 727. The Preamble says: “Whereas great numbers of people have of late seated themselves and their families upon and near the river Rappahannock, and the branches thereof above the falls; and great quantities of tobacco and other commodities are every year brought down to the upper landings upon the same river to be shipped off and transported to other parts of the

* Early Iron Manufacture in Virginia (Papers of U. S. Nat. Museum). By R. A. Brock, Secretary Va. Hist. Soc. The smelting-furnace near Fredericksburg is mentioned by Hugh Jones in his Present Condition of Virginia (1724).

country; and it is necessary that the poorer part of the said inhabitants should be supplied from thence with goods and merchandise in return for their commodites, &c.” It is also stated that the Spottsylvanians had petitioned the Assembly on the subject. It is therefore enacted that a tract of fifty acres belonging to John Royston and Robert Buckner should be vested in trustees and laid out for a town to be called Fredericksburg. The trustees were John Robinson, Esq., Henry Willis, Augustine Smith, John Taliaferro, Harry Beverly, John Waller, and Jeremiah Clowder — most of them old —baronial— names. Royston and Buckner, whose lands seem to have been unceremoniously taken, are to be paid forty shillings per acre. The price was probably not unfair, and no doubt those Gloucester gentlemen owned other lands whose value would be enhanced by the new town. They were to be paid from the money obtained by the sale of the “half-acre” lots! But the said Royston and Buckner are assigned two lots each. The owner of the land higher up and across the river was William Todd, of King and Queen County. He was given forty shillings per acre, assigned four lots, and allowed payment —for such houses as he hath erected, which shall be taken into any of the streets or public landings of the said town.&rduqo; The trustees of Falmouth were Robert Carter and Mann Page, esquires, Nicholas Smith, William Thornton, John Fitzhugh, Charles Carter, and Henry Fitzhugh.

All of these Falmouth names are historically connected with the immediate neighborhood, with a significant exception — Carter. This Robert Carter, who heads the list, resided at Corotoman, Lancaster ; he was an old man now, and, no doubt, practically represented on the Board by his son Charles; but nothing could be done in the Northern Neck save under his approval. For this was “King Carter,” agent in Virginia of the sixth Baron of Cameron, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, who inherited eight thousand square miles of Virginia from his mother, Catharine, daughter of Lord Culpeper. Colonel Carter before becoming “king” had led many troops against the Indians. These were nearly exterminated from the Northern Neck when he helped to found Falmouth. Besides his son Charles, his son-in-law, Hon. Mann Page, appears one of the trustees of Falmouth. His son of the same name built Mansfield, a grand house near Fredericksburg, and was father of the celebrated Governor Page, of both peaceful and revolutionary fame. Robert Carter, sometimes called “King,” but more popularly “Robin,” was as unpopular as an exact overseer of a vast estate traditionally associated with a royal robbery might naturally be. Though Culpeper had a bad name, Fairfax was in good repute; if any tenant was not satisfied, it was laid at old “Robin's” door.

The late Major Byrd Willis, of Fredericksburg, his great grandson, has preserved a bit of doggerel chalked on “King” Carter's tomb in Corotoman Church:

“Here lies Robin, but not Robin Hood,

Here lies Robin that never was good,

Here lies Robin that God has forsaken,

Here lies Robin the Devil has taken!”*

But the late John Minor — son of General John Minor, who married a daughter of Major Byrd Willis — adds a note in which he shows that there was no just ground for the unpopularity of Robert Carter. He also denies the tradition that Carter was dismissed from the Fairfax agency, and states that he held it until his death, which occurred in 1732. † In 1730, Lord Fairfax conveyed to Robert Carter a snug corner of the Northern Neck — 63,000 acres.‡ Majesty on the James dare not deal freely with Majesty on the other side of the Rappahannock. Ten years after King Carter's death, the Assembly passes a law against wooden chimneys in Fredericksburg, and the freedom of swine in its streets; nothing is said of the same evils in Falmouth. In 1755, Governor Dinwiddie reminds his Home Government that he cannot suspend fines and forfeitures in the Northern Neck. In 1763, it became necessary to abate the evils in Fredericksburg already referred to, and every wooden chimney was fined five shillings, every hog or goat in the street one shilling per month; the like evils in Falmouth being for the first time assailed in 1765, where, however, instead of being fined, the hogs and wooden chimneys are outlawed. They may be lawfully destoyed.

Fredericksburg, founded in 1727, the year in which George I. died, was named after the father of George III. It was not, however, incorporated until 1781, a new court-house being erected that year. “Having been

* Willis, MS. I am indebted to Mrs. Tayloe, of Fredericksburg, for the use of this invaluable manuscript left by her grandfather, Major Byrd Willis. It was written by that patriarch of the place for his own family only, but contains much of public interest

† John Minor, who writes this, was the most learned man that Fredericksburg has produced, as well as a gentleman of the most exalted character. He died in an early year of the late war.

‡ “Visiting his American estates about the year 1739 [Thomas Fairfax, Sixth Baron of Cameron] was so captivated with the soil, climate, and beauties of Virginia, that he resolved to spend the remainder of his life there; and he soon after erected two mansions, Belvoir and Greenway Court, where he continued ever afterwards to reside in a state of baronial hospitality. . . . He had been educated in revolutionary principles, and had imbibed high ideas of republican liberty.” — Sir Bernard Burke. The title devolved on cousins. The late Lord Houghton told me that when in this country he visited the eleventh Baron, and invited him to his seat in the House of Lords. It is remarkable that five of these American lords have unostentatiously borne witness to the principles of him whom the Duke of Buckingham described as, “Fairfax the Valiant.”

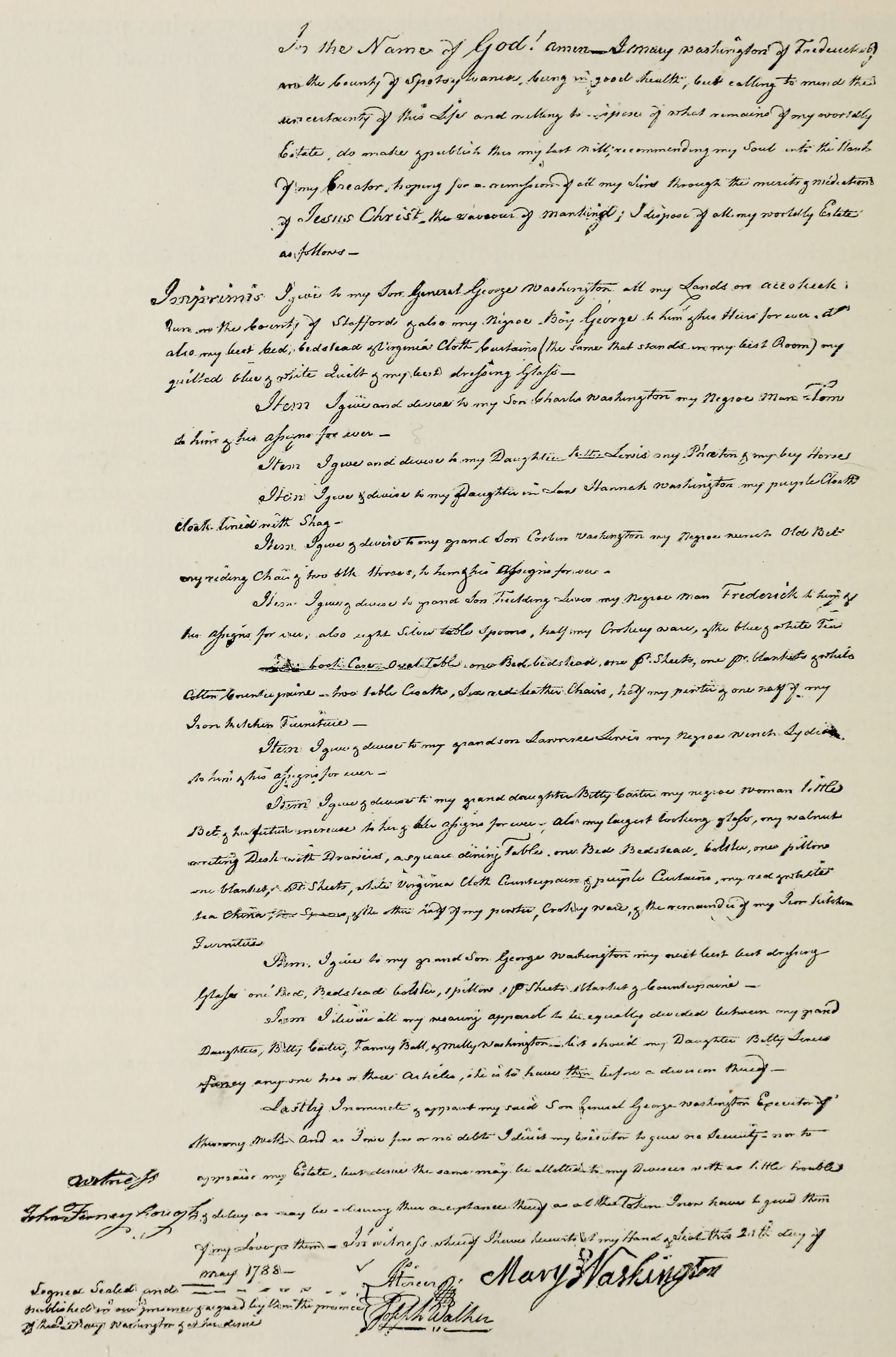

[Made directly from the original through the courtesy of the City authorities of Fredericksburg.]

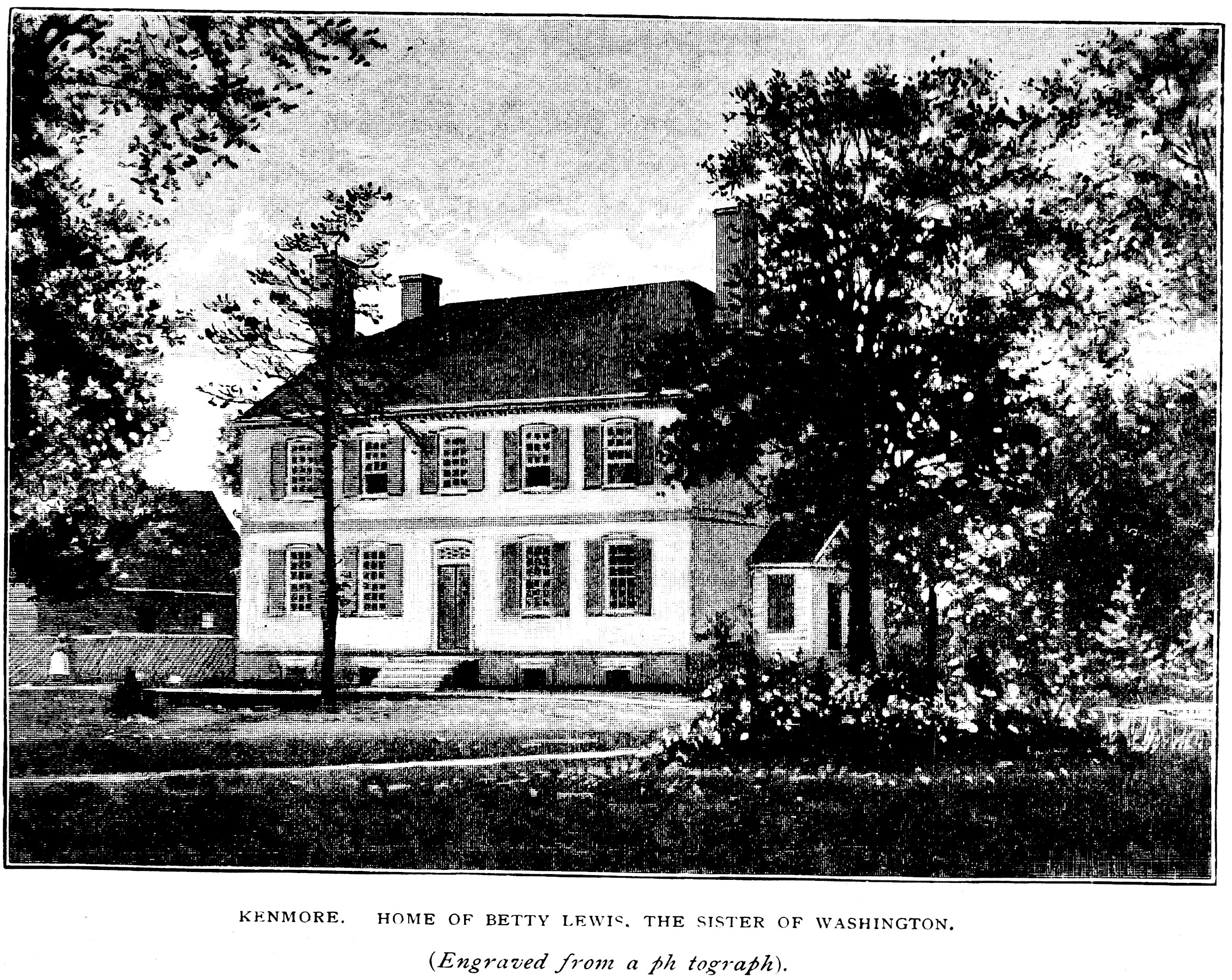

previously,” says Howison, “a village or collection of dwelling houses, inhabited by a variety of people, it was made a town according to a policy of the Government of Virginia which we now look back to with surprise. You know well that the tendency of the social system in Virginia, at least up to the time of the late war, was to country life, and not to the growth of towns. On their great landed estates, with their abundant means, their slaves and dependants, the gentlemen of the Colony, and afterwards of the Commonwealth, looked upon town life with something like aversion, and never sought the towns except for temporary business or pleasure. The General Assembly sought to antagonize this tendency. They sought to do a thing impossible — that is to make towns by statute-law.”* A good many of these paper towns came to nothing, of course. At the mouth of Potomac Creek there remains to this day the strong stone foundation of an edifice never built in what was to have been the town of Marlborough. But when the gathered population near the falls had been assigned the private property of certain gentlemen, and royally named, the Assembly did not regard it as quite respectable to transfer to it the Hustings Court, or give it a corporate council. Nor did the gentlemen interested in the foundation venture at once to dwell on any of the halfacre lots. The grand old residences, Mansfield (Pages), Fall Hill (Thorntons), and Kenmore (Lewises), Boscobel and Chatham (Fitzhughs), were all at a respectable distance. Even the chief gentleman and promoter of the town, Colonel Henry Willis, built his residence on the elevation

* Fredericksburg: past, present, and future. Lecture by Robert R. Howison, 1880.

beyond the town, since become historic as Marye's Hill.* The “great numbers of people,” in answer to whose needs the twin towns were founded, must have been at first mainly in Falmouth, for the fifty acres laid out as Fredericksburg were not yet well occupied in 1732, when Colonel Byrd visited the place after his visit to Governor Spottswood at Germanna, farther up the river. “Colonel Willis,” he writes, “walked me about his town of Fredericksburg. It is pleasantly situated on the South shore of Rappahannock River, about a mile below the falls. Sloops may come up and lie close to the wharf, within thirty yards of the public warehouses, which are built in the figure of a cross. Just by the wharf is a quarry of white stone that is very soft in the ground, and hardens in the air, appearing to be as fair and fine-grained as that of Portland. Besides that there are several other quarries in the river bank, within the limits of the town, sufficient to build a large city. The only edifice of stone yet built is the prison, the walls of which are strong enough to hold Jack Sheppard if he had been transported thither. Though this be a commodious and beautiful situation for a town, with the advantages of a navigable river and wholesome air, yet the inhabitants are very few. Besides Colonel Willis, who is the top man of the place, there are only one merchant, a tailor, a smith, an ordinary keeper, and a lady — Mrs. Leviston — who acts here in the double capacity of a doctress and coffee woman.”†

The real founder of Fredericksburg was the Colonel Harry Willis referred to by Colonel Byrd. He owned, besides his Fredericksburg estate, three thousand acres and a grist mill in the Little Fork of the Rappahannock, of which the patent was granted 1726;‡ but he was a careless and extravagant man, and when he died his property had to be offered for sale. Fortunately, his wife had saved enough to buy it up (Willis MS.). The Governor and Council, however, relieved this easy-going “gentleman of a

* My aged mother remembers the Willis House before it was burned. With the increase of the family, it had spread until it seemed a group of contiguous houses. The present mansion on the height, Brompton— not on the exact site of the Willis House, which was nearer the National Cemetery — was probably built by Colonel Willis, and altered by the late John L. Marye, the distinguished lawyer whose name is now connected with the Hill.

† Journey to the Land of Eden. The Levistons were the first residents of the place, and held their lease from John Royston, ©f Gloucester. They were persons of good position. Female doctors were not unknown in other parts of Virginia in early times. Colonel Byrd, in his journal, mentions another, a Mrs. Fleming, who explained to him her methods of treatment. The Rev. John Clayton, in a letter to the Royal Society, May 12, 168S, relates that "a gentlewoman that was a notable female doctress " cured a rattlesnake bite with oriental bezoar and dittany. (Force's Tracts, II.)

‡ Hening, IV., 464.

portion of his real estate, for when it was found, twelve years after the site was surveyed, that it occupied not only the original 50 acres taken from Royston and Buckner, but 243 square poles belonging to “Henry Willis, Gentleman,” and 220 belonging to “John Lewis, Gentleman,” the Governor, Council and Assembly removed “all doubts and controversies” by confirming these square poles to Fredericksburg, paying Willis five and Lewis fifteen pounds. Colonel Harry Willis was a very large man, as was his grandson, Major Byrd Willis, author of our MS. “It was said of my grandfather Colonel Henry Willis that he courted his three wives when

(Engraved from a photograph).

maids and married them all as widows. He had children by all.” “When the second wife died (she was the widow Mildred Brown when he married her) my grandmother, the widow Gregory, wept immoderately on hearing of it. Upon some one remarking that it was strange she should grieve so much for her cousin, she replied that the death of her relative was not the sole cause of her grief, though she loved her dearly, as they were cousins and bore the same name; but that she knew that old Harry Willis would be down there to see her, and she did not know what to do with him.” Sure enough, the old Colonel commenced a siege at the door of the Widow Gregory, sister of Augustine Washington. The fact that Henry Willis married in succession two cousins, christened with the same name — Mildred Washington ” induced Major Byrd Willis to believe that the first Washingtons were accompanied to this country by a brother unknown to history. (Lawrence Washington's daughter, Mildred, died in 1696). “He (the first John) left three children: John, who lived at the mouth of Machodock Creek (on the lower side), King George County. The property was afterwards sold by Thacker Washington. Whom he (John) married I cannot now recollect but I believe a Warner, as that was a favorite name among his descendants. The next was Augustine, who settled up Pope's Creek, Westmoreland at Wakefield (Bushfield?) where General Washington was born. I know not the name of his first wife, but his second was a Ball from Lancaster or Northumberland, in the Northern Neck: she was the mother of the General and of Mrs. Fielding Lewis, the grandmother of my wife. The third and last (of the first John's children) was my grandmother Mildred. My father, Lewis Willis, was a schoolmate of General Washington, his cousin, who was two years his senior. He spoke of the General's industry and assiduity at school as very remarkable. Whilst his brother and the other boys at play-time were at bandy or other games, he was behind the door ciphering. But one instance of youthful ebullition is handed down while at that school, and that was his romping with one of the largest girls; this was so unusual that it excited no little comment among the other lads.”

This Willis MS. proves that George Washington went to school in Fredericksburg. That, indeed, was but natural, for the farm where his boyhood was passed is within easy reach of the town. Among his schoolmates were some who afterward gained distinction under his command. Mr. Lossing's notion that Mary Washington's mother was born in Cookham, England, has been disproved by my brother, Richard Conway, who examined original documents connected with the subject. Colonel Joseph Ball, her father, married his first wife in England, and she died there, leaving him a son and four daughters. Before marrying his second wife in Lancaster, Virginia, he distributed some property to his daughters by the first wife. One deed, for 190 acres, to his son-in-law, Raleigh Chinn, is dated February 12, 1703, and witnessed by George Finch, Mary Johnson, and Edward Jefferys. On June 25, 1711, his will is dated, and on July 11 admitted to probate in Lancaster County, in it, after large devises of lands and slaves to his five children by the first wife, he writes: “Item, I give and bequeath to my loving wife Mary Ball, the feather-bed, bolsters and all the furniture thereto belonging, whereon I now lie in my own lodging chamber, as it stands and is now used, and all the chairs in the house which are single nailed.” He then devises to her land, slaves, crops, horses, cattle, hogs, sheep, stills, a chaise and harness, and an “Irish woman, by the name of Ellen Grafton, for the time she has to serve.” He then devises to Mary, his only child by his second wife (Washington's mother), “400 acres of land in Richmond county, in ye freshes of Rappahn. River &c.” Next we find: “Item, I give and bequeath unto Eliza Johnson, ye daughter of my beloved wife 100 acres of land, or what it is, more or less, that I bought of Webb Lux late of this county.” From this it appears that Colonel Joseph Ball married for his second wife Mary Johnson, a widow of Lancaster, with a daughter named Eliza; that by this second wife he had one child, born some time between 1703 and 1711, and named Mary, who became the wife of Augustine Washington.*

It may be that some future antiquarian will trace the path connecting the ancient village of Washington, Northumberland, England, to the parish of Washington, originally in Northumberland, Virginia. The former possesses fabulous fame as the place where the Knight of Lambton slew a dragon which desolated the country; the latter bears the name of a man through whom the fable, which may have fired the heart of some remote ancestor, was fulfilled.† The father of Washington owned a good property in Stafford besides his place at Fredericksburg, and he was interested, as we have seen, in an iron furnace. George Washington's precocity was not stimulated by poverty. His boyhood was passed in an interval of peace, except for the fierce conflict of sects brought on by the preaching

* See Washington Post, October 11, 1886. It is a curious thing to find Colonel Ball's gift to his son-in-law Chinn attested by Mary Johnson, who presently became his wife. Could she have been his housekeeper? The gifts to his children look as if he were conciliating his family. For many years one of the “characters” in Fredericksburg was a witty auctioneer named Gabriel Johnson, who was wont to summon people to his mart with Mary Washington's dinner-bell, and I have heard it suggested that he was a connection of her family.

† Mr. Alexander Brown, of Nelson County, Va., has unearthed the curious fact that in November, 1650, one George Washington was charged before the Bermuda Assizes with treason, for saying that “the King has sould his subjects to Popery” and “the King was a Rogue and deserved to be hanged 7 years ago.” George Washington was found guilty, but an appeal to England was granted. Mr. Brown points out that when the Virginia Company sold the Bermudas to the Somer Islands Company, they had to make good a deficiency of land by allotments in Virginia. By a paper filed at Whitehall (July 28, 1639), it appears that the consequent migration from the Bermudas was to lands “situate betwixt the Rapahanock and Patowmeck.” It is possible that one of the two Mildred Washingtons married by Harry Willis, the founder of Fredericksburg, was descended from this audacious anti-royalist of the Bermudas. There were several Washingtons in Stafford — Colonel William, Lawrence, Robert — whom the great General esteemed. The former he regarded as a relative, apparently without knowing the relationship.

of Whitfield and the presbyterian Samuel Davies. As for the Indians, their tomahawk was buried, as, indeed, were most of themselves. The old fort at Falmouth, as Governor Dinwiddie wrote, was long destroyed.* Two fairs per annum had been authorized for Fredericksburg (1738). The two towns had been largely settled by thrifty Scotchmen, who rapidly grew rich. The town attracted men of high intelligence. Dr. John Tennent, an able physician and botanist, who introduced Seneca snake-root in the treatment of pleurisy, wrote at Fredericksburg his important treatises, one of which was published by Dr. Richard Meade in Edinburgh (1738), and in the same city and in New York in 1842. He married a daughter of Rev. Archibald Campbell, brother of Alexander Campbell, father of the poet. Alexander was an early settler at Falmouth, where his wife was born. One of the poet's brothers, Robert, married a daughter of Patrick Henry, and Thomas was much grieved that he also could not reside in Virginia.

As the boy Washington watched the ships sailing past his home, the desire to go to sea grew within him; his mother would not allow him to accept the midshipman's warrant offered when he was fifteen, but was, no doubt, proud when, at seventeen, he was appointed by Lord Fairfax surveyor of the Northern Neck. It was a curious Nemesis that the high-handed donation of that region to Culpeper, the courtier, should have brought it into the hands of a nobleman at whose feet Washington learned a radicalism foreign to his own temperament. Although, when the final struggle came, Lord Fairfax adhered to the crown, and his estates were confiscated, his influence fostered the independent spirit of the Northern Neck — the cradle of the Revolution in Virginia.

One need only peruse the Dinwiddie Papers to know what leading part Fredericksburg and Falmouth bore in the English war against the French and their Indian allies. The supplies largely came thence, both of pro-

* Dinwiddie Papers, II. 475. Admirably edited and annotated by Dr. Brock, 1884.

visions and soldiers; also several leading officers were from these towns and their vicinity. In the year 1756, Stafford had a population of about 2,000 whites and a somewhat larger number of negroes, and Spottsylvania about the same. The wealth of the two towns — which might now be regarded as one — was large enough to attract the hungry eyes of royalty in England. The Stamp Act met with prompt and uncompromising resistance. The justices of Stafford resigned in a body, and sent to Governor Fauquier an address (dated October 5, 1765), in which they say: “Our County seal is his late Majesty sitting on his throne, with Justice and Mercy supporting his crown over his head, and this invaluable chapter of Magna Charta (which Ld. Coke says in his comment on the statute ought to be engraved in letters of gold in every Court of justice for its motto): ‘We will deny or delay no one justice’ — which we are firmly persuaded is inconsistent with the Stamp Act.”* This is signed by Peter and Travers Daniel, Wm. Bronaugh, J. Alexander (Burgess 1767-75), Wm. Brent (descendant of the famous Giles Brent, Lord of Kent Island, Maryland), J. Mercer, author of Abridgment of the Laws of Virginia, and founder of a distinguished family, Thomas Ludwell Lee, member of the Convention of 1776, and judge of the General Court, Samuel Selden, Gowry Waugh, Thos. Fitzhugh, of Boscobel, near Fredericksburg, and Robert Washington, to whom General Washington bequeathed a spy-glass and gold-headed cane.

In this emergency of the Stamp Act, the town of Falmouth, which had perhaps a thousand inhabitants, formed a committee, and moved with such energy as to elicit a snub from Richard Henry Lee, who, in a letter preserved in the Philadelphia Phil. Soc. Library, writes: “When a Committee has already been chosen for the County of King George by the Freeholders after full and fair and sufficient notice it is surely subversive of every idea of propriety that a small village like Falmouth should presume to have a Committee of their own partial and private election.” Whether because they heard of this movement in Falmouth, or for other reasons, the British Government repealed the Stamp Act, but with a declaration of their right “to bind the colonies and people of America in all cases whatever.” This, too, was soon to be tested.

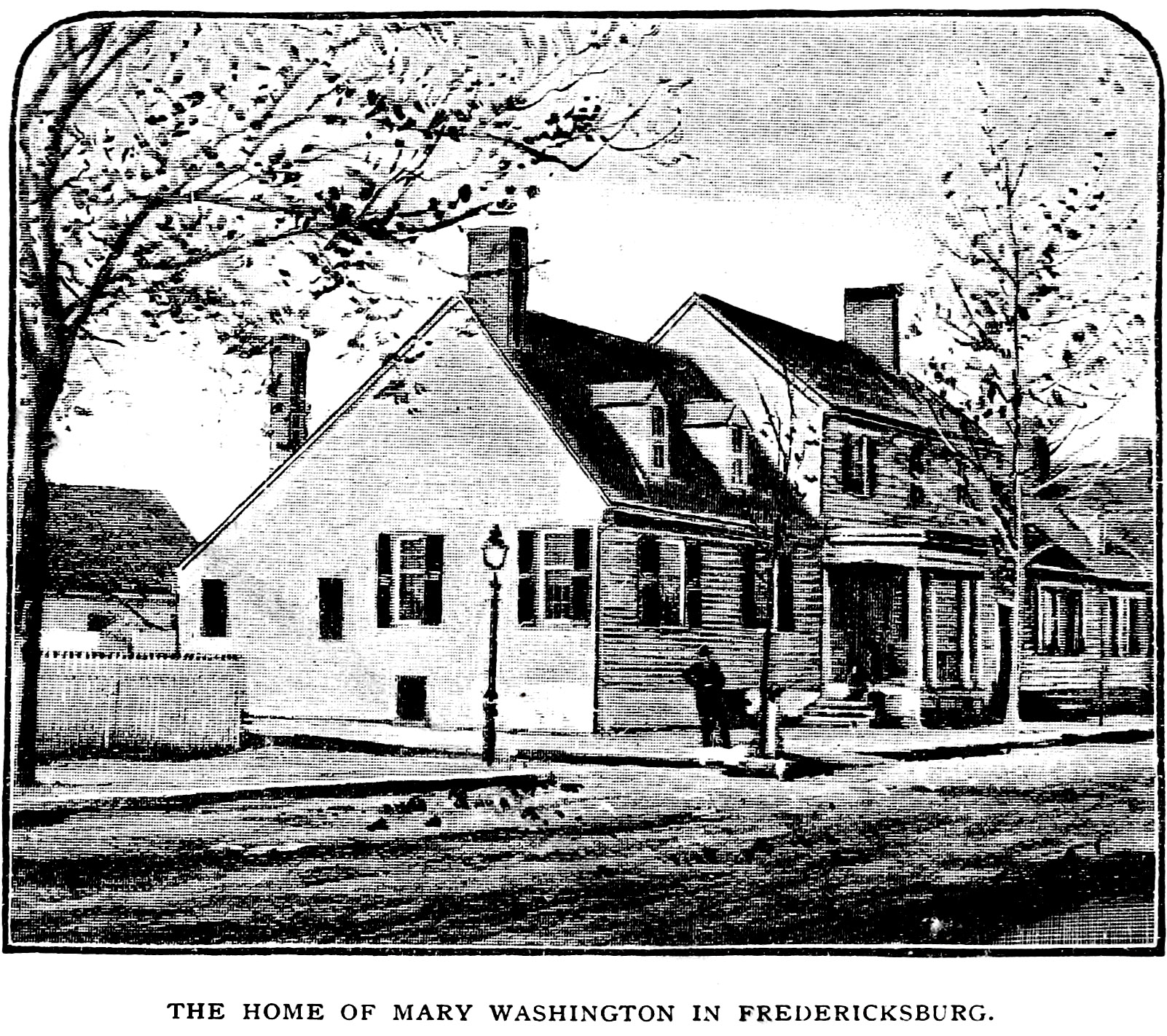

The society gathered at Fredericksburg about this time was unique. Mrs. Washington had moved, about 1750, to her house in Fredericksburg, not very far from Kenmore, where her daughter Betty (Mrs. Fielding Lewis) resided. Colonel Fielding Lewis, a worthy magistrate and legislator, owned

* It is worth noting that in the course of this address these magistrates mention as articles supplied to the mother country tobacco, wines, flax, hemp, silk, iron and potash. All of these industries flourished in Virginia. Wine was made by the Huguenots.

half the town. St. George's Church, built in 1732, had grown strong under a succession of brilliant clergymen — Patrick Henry, uncle of the famous statesman, James Marye, a Huguenot refugee, who was transformed to an Episcopalian and preached there thirty-two years, and an eloquent son of the latter, bearing the same name. There could hardly be imagined men more adapted to keep alive the spirit of independence. The descendants of Governor Spottswood resided there, as indeed they do to this day.

There were two families of Mercers in the place. One was that of the celebrated General Hugh Mercer, who, after his eminent service at Pittsburg and elsewhere in the Indian and French wars, had settled down to a large medical practice. Hugh Mercer had fought for the Pretender at Culloden (1745), then fled to Fredericksburg, where he was the hero of George Washington, aged 14, under whom he was destined to do heroic service. He was in the Indian wars ten years later, was wounded at Fort Duquesne, and barely escaped capture. Mr. Dreer, of Philadelphia, has a letter by him, dated Fredericksburg, May 16, 1767, acknowledging his election as a Corresponding Member of the Philadelphia Medical Society, and giving some interesting information as to the methods he had used in certain diseases to which his neighborhood was liable. The fine face which the pencil of Trumbull has preserved of this brave general, who fell at Princeton (January 3, 1777), bears a resemblance to some members of another family of Mercers, though the relationship between them has not been traced. These were descended from an Irish gentleman of wealth who settled in Stafford, 1720. One of his sons, Lieutenant-Colonel John Fenton Mercer, raised a squadron of horse in that county at his own expense, fought beside Lafayette, and sat in the Constitutional Convention.* Colonel George Mercer, who had been solicitor in London for the Ohio Land Company of Stafford, was appointed Stamp Collector, but soon resigned (Emmet MS.). The house of the Mercers at Fredericksburg was called St. James. Here Judge Mercer, whose name is attached to Mary Washington's will, dispensed a grand hospitality. He married a Miss Dick of Fredericksburg. To Captain Charles Dick, chiefly was entrusted the manufactory of arms established at Fredericksburg in July, 1775. General George Weeden, made Brigadier-General Feb. 21, 1777, had been host of the “Rising Sun Hotel,” where he had often entertained Colonel George Washington and other distinguished gentlemen of the neighborhood — among them Richard Henry Lee, who organized the anti-Stamp-Act Association, and young George Mason, who had talked his Declaration of Rights a score of times

* His daughter Margaret impoverished herself by liberating her slaves, and supported herself by teaching until her death in 1840.

at the “Rising Sun” before he put it on paper. Dr. Smyth, in his book of travels in America (London, 1784), says that he stopped at the hotel kept by George Weeden, “who was then very active and zealous in blowing the flames of sedition.” James Madison, born at Port Conway, near by, liked to visit the town of culture and fashion. It had a Jockey Club. Freemasonry was also one of its fashions. Washington was initiated into the Lodge there November 4, 1752, and made a Master Mason the year following. Fredericksburg was the Masonic centre for twelve counties. The Lodge was a nest of “treason.” It is not wonderful that in such a community the revolutionary spirit was found already panoplied when Lord Dunmore removed the gunpowder from Williamsburg to his man-of-war. Six hundred men then armed themselves and offered their services to defend their capital. A council was held, and on April 29, 1775, a Declaration of Independence for Virginia and her sister colonies was passed, concluded with the words: “GOD SAVE THE LIBERTIES OF AMERICA.”