The Washington Star, Sunday Morning, July 4, 1937, Page F–1

RESTORED CIVIL WAR FORT IS NEW SIGHTSEEING SHRINE

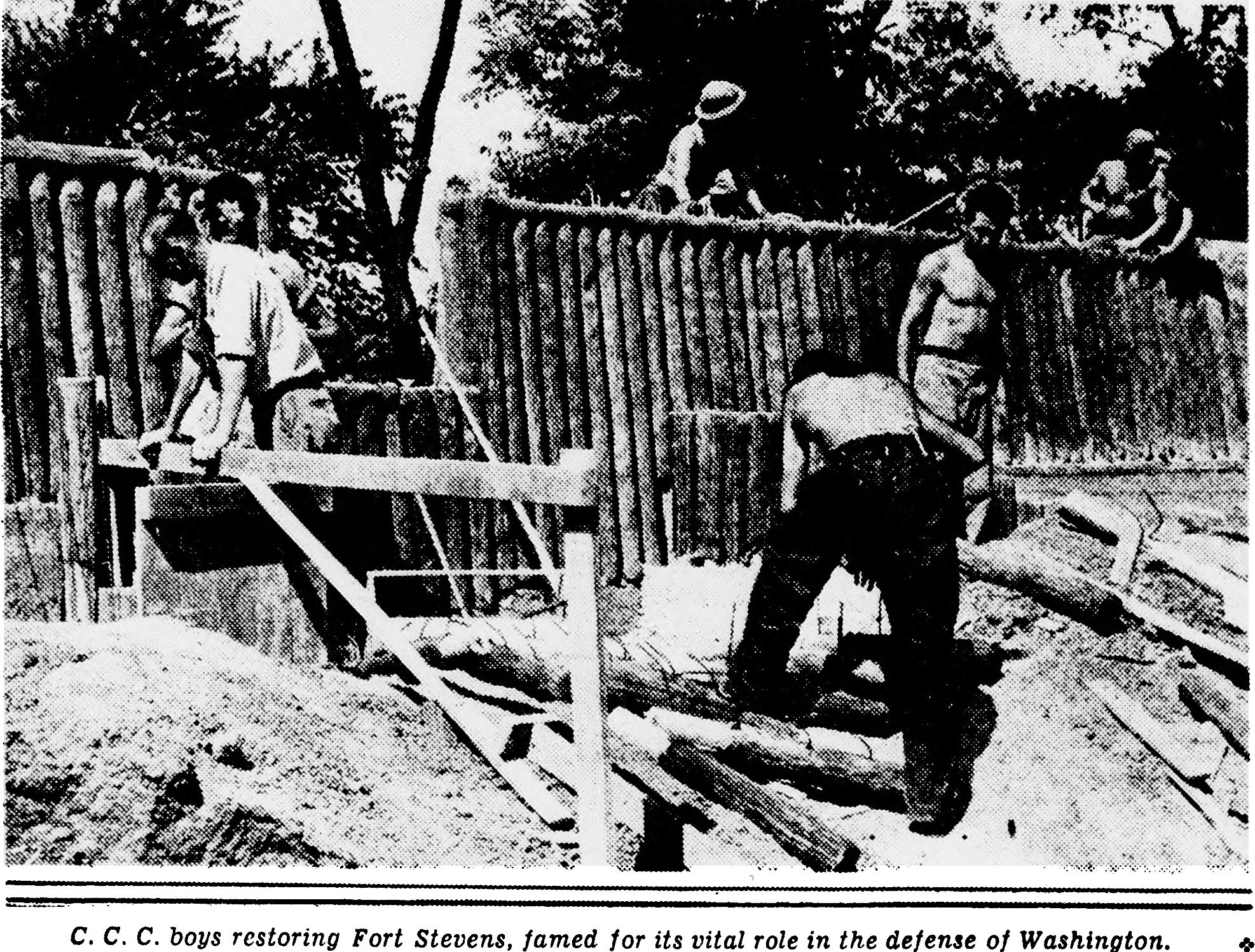

C. C. C. Boys restoring Fort Stevens, famed for its vital role in defense of Washington.

Fort Stevens Played Vital Role in Defending Washington From Confederate Invaders in July of 1864—Lincoln, Only President Ever Under Combat Fire, Was Present.

By Bernard Kohn.

HISTORIC Fort Stevens, famed for its vital role in the defense of Washington during Civil War days, is rising again. Aroused from its 72-year slumber by the picks and shovels of a small army of busy C. C. C. youths, the fort, located near the District of Columbia's northern rim, is being reconstructed under the direction of the National Park Service.

Already parapets and rifle-pits have replaced barren age-worn earthworks once found at the renowned site. Soon the muzzles of authentic Civil War cannon may be seen pointing through the yawning embrasures of the fort's wall. As the restoration rapidly nears completion, public spirited citizens eagerly look forward to the time when Uncle Sam will officially open this new shrine for sightseers in the Nation's Capital.

Gnarled, battle-scarred veterans pause at the restoration site to watch the industrious C. C. C. workers who, in their blue denim attire are veritable modem boys in blue. Dimmed eyes sparkle again, as the bent graybeards think back upon bitter campaigns or, perhaps, sentry duty at some lonely outpost.

Every day, as curious passers-by clamber over the entrenchments, they readily envision exciting days of the past when Minie balls whined overhead and sharpshooters harassed the enemy with deadly fire. Every one finds something of special interest at Fort Stevens. Historians and military engineers gain a wealth of technical information. Teachers and students discover that historical facts and dates assume a new meaning. Even neighborhood children at play find the place thrilling. Innocently enough, with childish glee, they brandish toy guns and climb over the parapets to engage in mock warfare.

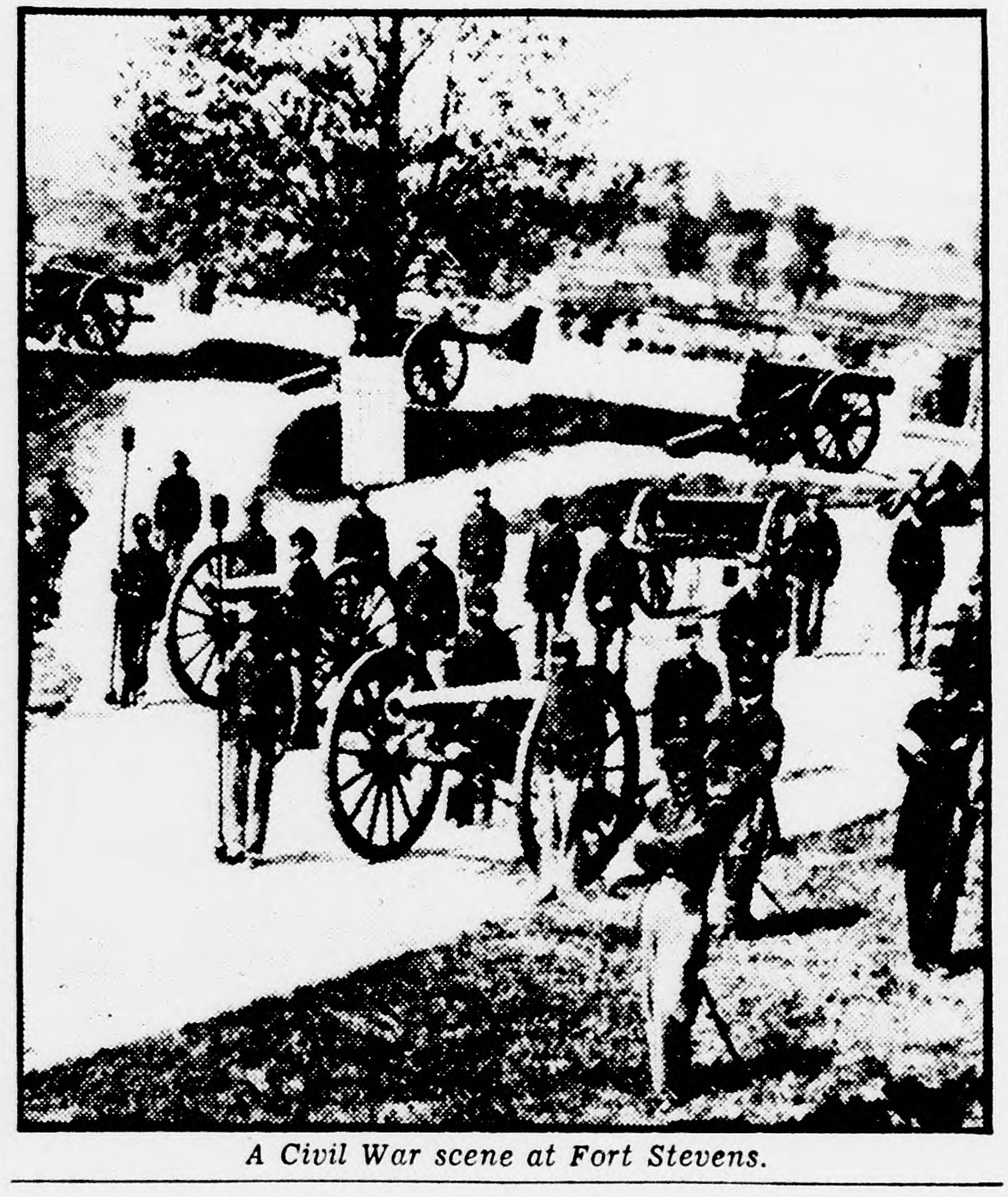

A Civil War scene at Fort Stevens.

But no one is more enthusiastic than Robert R. McKean, National Capital Parks landscape architect, who is supervising the development of the reproduction. Ever since Uncle Sam started to rebuild the glamorous old fort, McKean has been on the scene of activities. Indeed, the story of the restoration is the story of Robert McKean's untiring efforts.

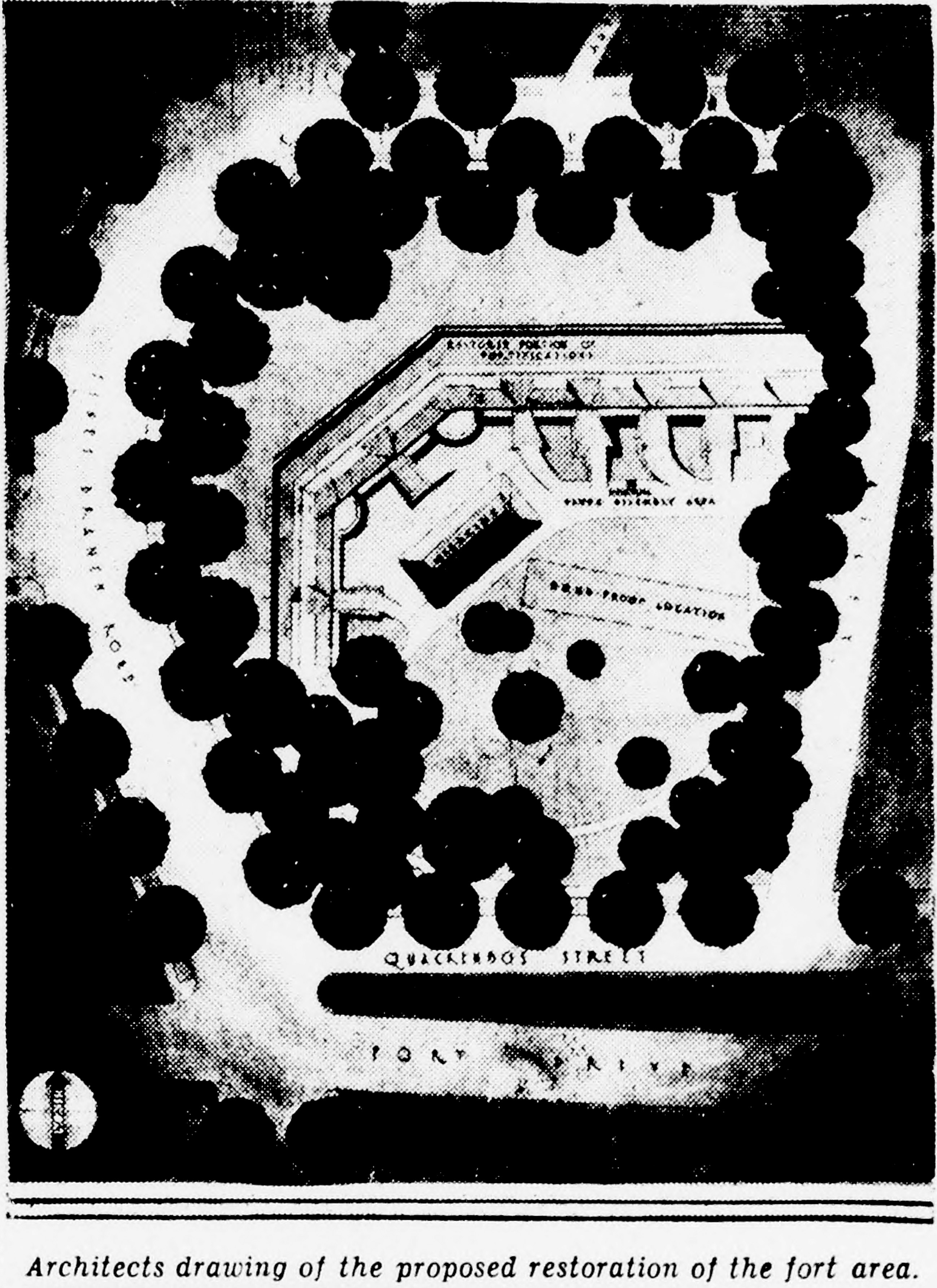

Architects drawing of the proposed restoration of the fort area.

An Inspection tour of the area with McKean as host is a real treat to the visitor. “Fort Stevens will not be restored in its entirety,” says McKean. “During Civil War days,” he continues, “the defense embraced more territory than the area owned by the Government today. Originally the place was called Fort Massachusetts. Later it was enlarged and named to honor Maj. Gen. Isaac Stevens, Union war hero.”

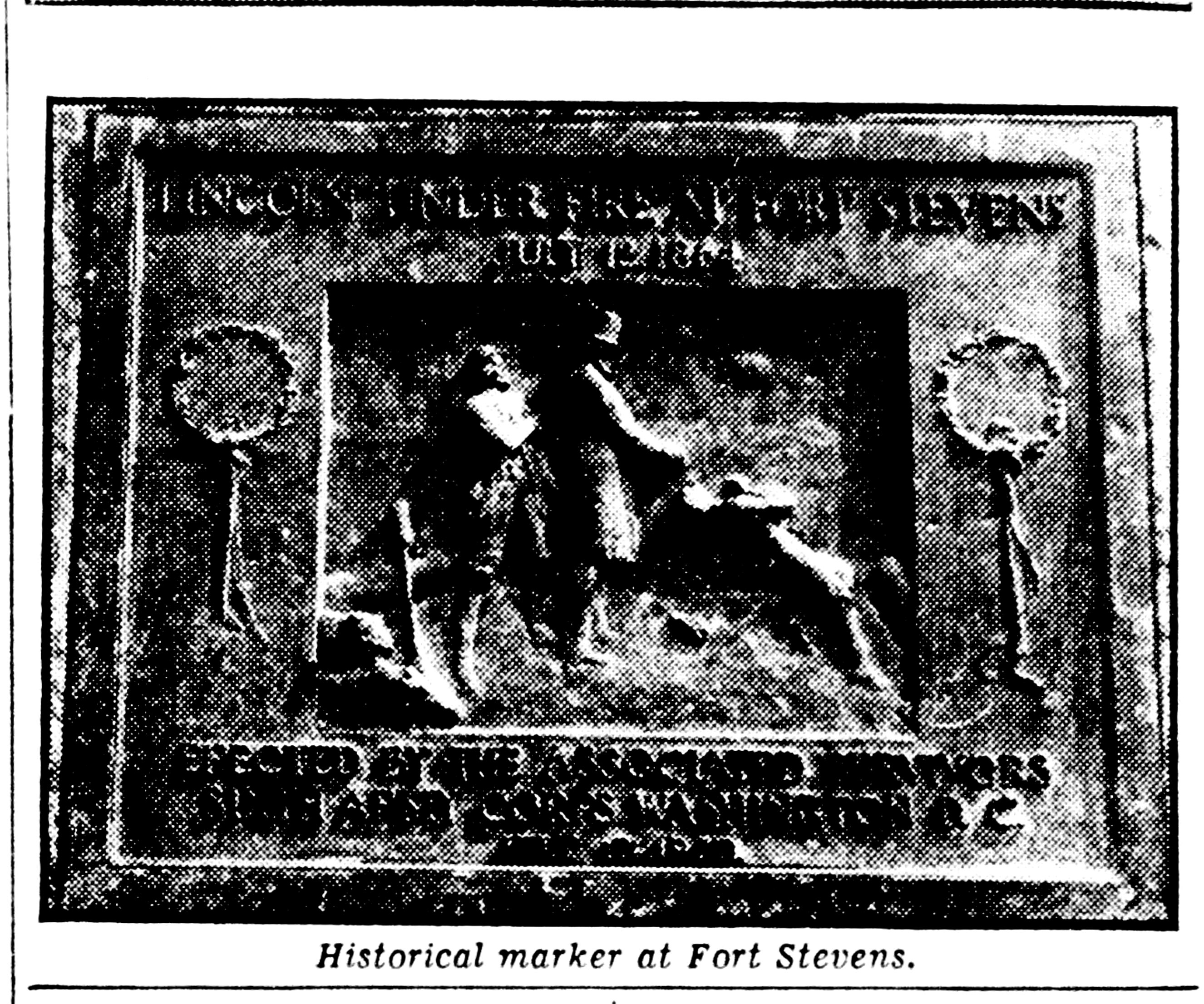

Historical marker at Fort Stevens.

Pausing beside the log parapet, the architect asks his guest, “what kind of wood is used in the fort wall?”

This question never fails to stump the sightseer, whether he be noted botanist or John Q Layman. With a twinkle in his eyes, McKean explains that the “logs” are made of concrete, not wood! Little wonder the visitor is incredulous. Only close examination of the “logs” reveals that the “bark” is dark-colored cement cleverly applied by deft artisans. These simulated logs, McKean says, last far longer than natural wood.

Replacing the artillery at Fort Stevens will be an easy matter. Accurate accounts of the fort's ordnance were found in old military reports. Upon the gun platforms, recently completed, will be mounted nine cannon in the same strategic positions as in war days. In those tumultuous times, a total of 20 heavy guns protected the fort with their death-dealing messages.

Conspicuous on the grounds is the powder magazine, now under construction. Here McKean pauses to tell the legend of Aunt Betty Thomas, a colored woman who lived in a tumbled down log cabin located on the spot now dominated by the magazine.

When war loomed in 1861. Army engineers decided to enlarge the original works and ordered Aunt Betty to quit her homestead. But she refused to budge! Then one day while inspecting the fort, Lincoln heard of the difficulty and sent for the defiant woman. Standing under a towering sycamore, the President gently explained to her how vital was Fort Stevens in the Capital's line of defense. He promised her due compensation for loss of land and home. Then, won by his kindly manner, she packed her belongings and departed. Today, the sightseer may stand under the spreading limbs of the same tree where Lincoln eased the breaking heart of Aunt Betty.

ANOTHER feature of the original fort, McKean points out, was the bombproof structure which sheltered soldiers from curving artillery fire. In this long, narrow log building, weary infantrymen, in comparative safety, snatched much-needed sleep after long vigils at their posts. The bombproof location is within the limits of the restoration area, but no definite steps have been taken to reproduce the ancient refuge.

So the tourist may see the layout of the entire defense, a bronze model of old Fort Stevens now is on view at the historic shrine. This tablet, erected by the Daughters of the Union Veterans of the Civil War, is mounted on a granite pedestal and dedicated to the memory of the blue fighters.

Another memorial, long a landmark at the fort site, is the rugged granite monument which commemorates Lincoln's dramatic experience at the Battle of Fort Stevens. During the fight, with utter disregard for his own safety. Lincoln stood upon the parapet where he could better observe the Confederate attack. Not until a surgeon at his side was felled by a Minie ball, did he shield himself behind the breastworks. It is the only time a President of the United States has been under combat fire. Today, this gripping incident is depicted in bas-relief upon the bronze plaque of the marker.

Modern visitors, standing on the spot hallowed by Lincoln, look upon a scene vastly different from that viewed by the anxious eyes of the wartime President. Then, except for an occasional farm house, the long, rolling reaches of green pasture lands were unbroken. The staccato beat of horses, hoofs rang through the air as grim troops of cavalry dashed along dusty roads. Now, the fort site is hemmed in by brick dwellings, apartment houses, churches and schools. Sleek, purring automobiles whiz along smooth highways which surround the historic place.

DESPITE the encroachments of civilization, the fort's high position affords visitors a commanding view of the distant countryside. To the northward is a tree of deep historic significance. The weather beaten sign nailed to the trunk tells the story: “Site of the Toll Gate House nearest point to Washington reached by the Confederate troops under Gen. Early in the Battle of Fort Stevens * * *”

President Lincoln inspecting Fort Stevens during battle on July 12, 1864.

Historical Heritage of Old Stronghold Inspired Reconstruction for Which Original Specifications Were Discovered— the National Park Service and C. C. C. Are Doing Work.

Boys in Blue at Fort Stevens during the Civil War.

This famous landmark is located at Piney Branch road and Georgia avenue, approximately one-quarter of a mile from the fort. The restoration area is destined to become famous for its recreational as well as its historic appeal. Large shade trees, shrubs and fresh green expanses will offer a pleasant retreat from jammed thoroughfares of the bustling city. Numerous rustic benches will invite strollers to relax in this serene spot where once ensued a bloody struggle. For the convenience of patriotic organizations which come here for celebrations, a paved outdoor assembly plaza will be installed.

To McKean the restoration job is an exciting architectural experience. This readily is understood when the dark-haired, soft-spoken artist looks back upon various phases of the work.

After National Park Service historians chose Fort Stevens as a representative example of a Civil War defense. McKean rolled up his sleeves and launched a vigorous search for accurate data about the works. He surrounded himself with musty old volumes that fairly exuded glowing tales of heroism and fierce conflicts. Patiently he interviewed white-haired veterans and examined thousands of yellowed photographs depicting Army life in the '60s. “All this information was intensely interesting.” says McKean, “but we wanted something more tangible— such as plans, elevation views and dimensions of the old fort.”

FINALLY McKean's zealous search was rewarded. Original drawings of Fort Stevens were uncovered here in Washington by War Department officials. Brought to light again after many years in dusty files, the patched, spotted sketches revealed: specifications of the fort's construction.

The discovery of these sketches was indeed fortunate. Unlike many other restoration jobs where engineers were guided by slim clues, the local project is favored by a four-fold check on accuracy of data—drawing, photographs, verbal descriptions and well preserved earthworks.

Despite the fact that McKean's talented efforts are evident— at every turn, he disclaims any credit for the excellent development of the fort.

“We were extremely fortunate,” he says, “in being able to find the old records. Naturally, the primary aim in a project of this kind is authenticity. In this I feel we are succeeding. Then, too, co-operation between the C. C. C. and the National Park Service and the sympathetic understanding of our problems among all who shared in the

(Continued on Sixth Page)

Page F–6

NEW WAR SHRINE

(Continued From First Page)

work gives assurance of a job well done.”

After McKean and his associates were armed with the valuable data, they began a survey of the remaining breastworks at the site. Scale drawings of existing topography and original sketches, when placed side by side, dovetailed neatly. Before long, excavation work got under way.

This phase of the job proved intensely interesting to the C. C. C. enrollees. Their imaginations were stirred and pulses quickened when workaday shovels uncovered long buried war relics— uniform buttons, battered canteens, bullets and bits of shells. At times, freshly upturned earth disclosed bark fragments of the original parapet. In fact, the various finds are of such archeological merit they may be exhibited in a museum that park officials hope to erect later.

EVEN the concrete base of the Lincoln monument yielded an interesting cache. Recently when the marker was removed temporarily, workers found a copper box containing shiny medals, rare photographs, old newspapers and other patriotic mementoes. The souvenir chest, first buried in 1920 when the Sixth Army Corps Association erected the tablet, has been replaced in the memorial's foundation.

One of the most exciting phases of the restoration job. McKean says, was his talks with Civil War veterans and their contemporaries. Since the ranks of the Blue and Gray survivors are thinning fast there are today few people alive who remember Fort Stevens of the war era, but from seasoned cavalrymen, drummer boys, flag bearers and sharpshooters. McKean heard many thrilling tales. Surprisingly, the most fascinating story was told not by a grizzled campaigner but by a gentle, silver-haired woman who resides on Georgia avenue near Rittenhouse street at the edge of the restoration area— Mrs. Anne Osborn.

Her experience is unique. All her life this 81-year-old native has lived in the immediate vicinity of the fort. As a child she was present, when the Union men threw up the defense. Down through the years she watched the structure fall into ruin. And now she looks upon its rebirth— a rebirth inspired by a rich historical heritage which she saw in the making. Poignant memories come swirling out of the misty past and it is with mingled emotions that Mrs. Osborn watches the fort rise again. The careful progress of the work strangely contrasts with the feverish haste which marked Union construction activities. Today, she muses, the embattlement is a source of enjoyment to every one. This is a queer reversal of the forts destiny. During the war the erection of Fort Stevens caused much anguish, even among true blue patriots.

AS SHE sways back and forth in her rocking chair, beshawled Mrs. Osborn harks back to the days when men in blue dominated the local scene. “My father’s 13-room house,” Mrs. Osborn recalls, “was burned down to make space for the fort. I was only 7 then but I remember distinctly how I tugged on dad's coat and told him that a soldier with a flaming torch was coming to set fire to our house. It was true. The Union engineers found it necessary to destroy our home as well as nine others. Believe me, there was much wailing among the womenfolk when they saw their homes go up in smoke.^”

There were happier days, though. Mrs. Osborn's keen eyes twinkle when she tells of times when her mother bedecked her in her best bib and tucker and they strolled up to Fort Stevens to watch the soldiers drill. She was a favorite with the men. Sometimes a good-natured officer would allow her to “fall in” and march in the Blue ranks.

During the Battle of Fort Stevens the Osborn family lived in a tiny shack located where today stands the Brightwood car barn. “We were quite close to the fighting.” Mrs. Osborn reminisces, “and things were pretty hot around here.”

And “pretty hot” was right!

Washington citizens were alarmed when news arrived that Gen. Early's 15,000 Confederate troops had scattered Lew Wallace's men at Monocacy and were advancing on the Capital. July 11, 1864, found the Gray hosts at the northern outskirts of the city. Finding the city&aos;s forts feebly-manned, the Southern general ordered his men to rest for an attack the next day.

This delay was fatal.

Until then Washington's defense had been not much else than citizen soldiery. Calls for volunteers had been spread in all directions. In order to make an impressive showing of manpower, wounded soldiers were taken from their beds and civilians from their work. Hurried by urgent orders of Gen. Grant, the 6th and 19th Corps had arrived by land and water.

The Union's ruse was successful.

When Gen. Early surveyed the situation the next morning he was amazed to find the hitherto empty fort bristling with armed soldiers. Despite the hopeless outlook, he sent his forces into action. But regiments of Blue fighters, dashed from the Union's advance line and after hot skirmishing overcame the enemy's stubborn resistance. Early's chance of making “the most brilliant stroke of the war” had vanished.

Restored Civil War Fort is New Sightseeing Shrine, by Bernard Kohn, The Evening Star, Sunday Morning, July 4, 1937, Pages F–1 & F–6. (PDF)