Carbon County News, Red Lodge, Mont., July 07, 1939, Page Two.

Lincoln the Only President Ever Under Enemy's Fire While Holding Office of Chief Executive; It Happened at Fort Stevens Just 75 Years Ago.

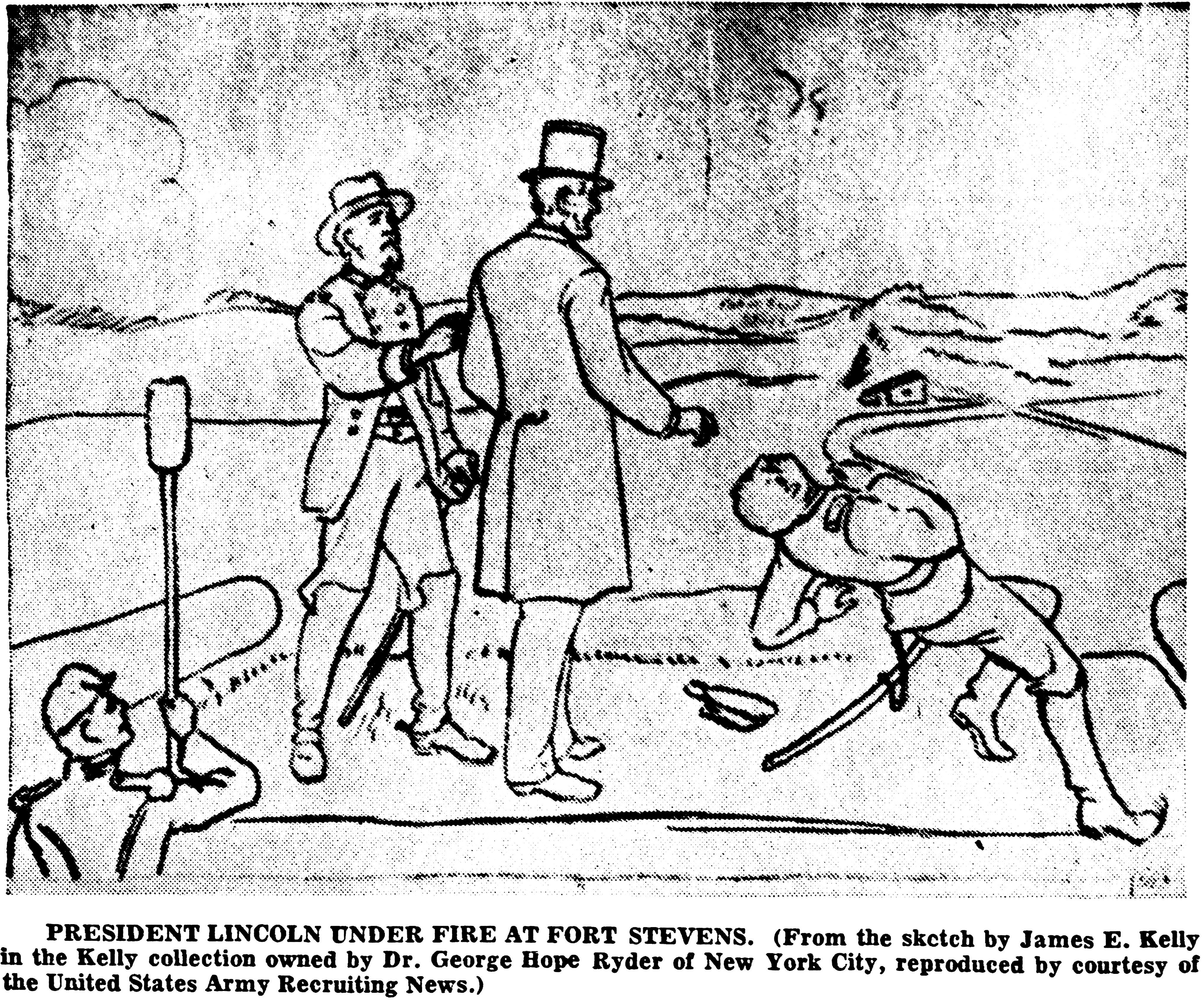

PRESIDENT LINCOLN UNDER FIRE AT FORT STEVENS.

By ELMO SCOTT WATSON

(Released by Western Newspaper Union.)

SEVENTY-FIVE years ago this month a President of the United States stood on the parapets of a fort and heard the bullets of enemy soldiers whistling about his ears— the only case on record of a Chief Executive having that experience during his term of office. The President was Abraham Lincoln and the scene of his narrow escape from death was Fort Stevens on the outskirts of Washington July 12, 1864. It came about in this way:

It came about in June of that year Grant began his famous “hammering“ campaign against Richmond which drove Lee back upon Petersburg. By the first of July it seemed certain that Petersburg was doomed and when it fell the door to the capital of the Confederacy would be opened.

Realizing that Grant was not to be beaten off by direct assault, Lee decided to make a threatening gesture toward Washington.

He sent Gen. Jubal A. Early and 30,000 picked men to the Shenandoah valley to sweep down upon Washington from the north. Early had reached Martinsburg, W. Va., before Grant became aware of what was taking place. Immediately the Union commander ordered small detachments of cavalry into the valley to harass Early and delay him until he could bring the Sixth Army Corps to the rescue of the capital. Next he ordered Gen. Lew Wallace, who was at Annapolis with 8,000 “hundred-day men&rdqou; to intercept Early at Frederick.

Sweeping up the Shenandoah, Early crushed a small Union force commanded by Gen. Franz Sigel, swung off to Maryland Heights and bottled up another force led by General Weber. On July 5 he crossed the Potomac and the next day captured both Hagerstown and Frederick. On July 8 he met Wallace's green troops on the banks of the Monocacy and, although he defeated them decisively and scattered them, Wallace partially accomplished his purpose of delaying the invaders for a little while.

Then Early began making forced marches. July 10 found him at Rockville and the morning of the eleventh his cavalry reached Silver Spring, on the outskirts of Washington, with the main column close behind. Washington was protected by 29 forts and 11 batteries on the south; 12 forts in Anacostia; two at Chain Bridge and 19 forts and 23 heavy batteries on the north. All of these fortifications were connected by deep rifle pits and had heavy guns, but Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, commander of the Washington defenses, had fewer than 3,000 men in his garrisons.

As Early's troops approached the city along the Seventh street pike, a force of Federal cavalry was sent to meet the invaders. But these were soon beaten back and Confederate sharpshooters, taking possession of houses along the pike, began pouring a murderous fire into the rifle pits into which General Wright had rushed all his effective troops.

Meanwhile Wright had been combing the hospitals in Washington and every man who could walk was put into uniform and pressed into service. The Union commander marched these troops back and forth in full view of the Confederate lookouts, moved them from fort to fort and changed their positions in the rifle pits frequently to give an impression of a great force of troops in reserve. Then, just as the Confederates started to deploy along a two-mile front for a concerted attack, Wright attempted a magnificent bluff.

A skeleton regiment of 400 men of the Twenty-fifth New York dismounted cavalry, commanded by Captain Chamberlain, which had just arrived from Baltimore, where it was being remounted and reorganized after being cut to pieces during the fighting in Virginia, filed into the rifle pits. Suddenly they leaped out, and, yelling like demons, charged through the picket line, drove back the Confederate skirmishers.

GEN. JUBAL A. EARLY

and recaptured the stone houses where the Gray sharpshooters were hiding. Acting as though Grant's “Invincible Sixth Corps” were backing them up, instead of a few thousand ineffective troops, they completely fooled the invaders and stopped their advance.

Early hesitated—and let slip his golden opportunity to capture Washington and perhaps end the war. As the forts increased their fire he began to withdraw his troops. A few hours later Grant's veterans marched into the capital. Washington was saved!

That night there was heavy skirmishing in what is now Rock Creek park and Brightwood with the guns of Fort Stevens and Fort De Russey still roaring defiance at the invaders. During the night Early learned from his spies how he had been fooled and, filled with rage at the thought of his lost opportunity, he resolved to renew the attack despite the arrival of the Union reinforcements.

On the morning of July 12 he again advanced to the attack, after sending his sharpshooters forward to open fire on the defenders of the forts. During the morning President Lincoln arrived on the scene in his carriage, accompanied by Mrs. Lincoln. As General Wright advanced to greet him, the President extended his hand, saying, “General, I am very glad to see you. This looks as though we were going to do something.”

“Mr. President,” replied the general, pointing toward Fort Stevens, “if you'll just come along down there with me, I'll show you one of the prettiest little fights you could wish to see.”

Years later, General Wright told of the historic incident thus:

“No sooner were the words out of my mouth than I deeply regretted having uttered them. I fully realized that the President's life was far too valuable to be brought into danger by any careless words of mine, But it was too late. He not only accepted my invitation but insisted upon accompanying me, notwithstanding all I could say to prevent him. He sent his wife back and when I mounted the parapet, there he was beside me, looking out upon the scene with a great deal of interest. The enemy's sharpshooters were firing pretty closely, and I explained to him that the place was entirely too dangerous for him.

“‘It is not more dangerous for me than it is for you,’ he replied coolly.

“‘But it is my duty to be here while it is your duty not to expose yourself. Your position requires this, and I particularly request you to remember it.’

“Just then a sharpshooter's bullet struck a surgeon who standing near the President and I became really alarmed for his safety and I have no doubt, a little excited, as I said firmly:

“‘Mr. President, you must really get down from this exposed position. I cannot allow you to remain here longer and if you refuse I shall deem it my duty to have you removed under guard.’“I suppose the absurdity of my threatening to put the President of the United States under arrest amused him, for he smiled, looked at me quizzically and got down behind the parapet, where I provided him with an ammunition box for a seat, but he wouldn't sit still a minute at a time and was constantly stretching up his long form to see what was going on, thereby exposing fully half of himself to danger in spite of all could do; and thus he continued to bob up and down until the action was over, when he cheered lustily along with the rest and bidding us good night, got into his carriage and rode away home.’”

Soon afterwards the whole Confederate line moved forward but counter-attacks from Fort DeRussey drove the flanks in toward Fort Stevens. Despite the hot fire poured into the Confederates they advanced to within a short distance of the rifle pits before their lines broke and retreated.

Under the cover of darkness General Early withdrew his forces and crossed over into Virginia at White's Ford into Loudoun county. His retreat was a masterly one and was accomplished with such skill that the Union forces were not aware of his withdrawal until he was too far away to be overtaken.

In recent years a reproduction of old Fort Stevens, whose valiant defenders saved the nation's capital 75 years ago, was constructed by CCC workers and today a granite monument marks the spot upon which Lincoln stood as he watched the fighting. A bronze tablet on the monument reproduces the historic scene of July 12, 1864 the only time an American President was under combat fire while in office.

GEN. HORATIO G. WRIGHT

This bronze tablet was executed from a sketch made by James E. Kelly, a famous sculptor and artist of Civil war scenes. Early in 1896 Kelly was in Washington while his model submitted in competition for the proposed equestrian monument of Gen. W. T. Sherman was on display in the war department. At that time Wright, who had been retired from the army was in the capital. Kelly had known Wright while both were living in New York during the seventies and had made a medallion portrait of him.

On January 17, 1896, the artist accompanied the general to the site of Fort Stevens near Brightwood, D. C., and there, under Wright's direction, he sketched the picture of Lincoln standing on the parapet of Fort Stevens, exposed to the fire of General Early's sharpshooters. That picture, signed and dated by Wright, is now in the possession of Dr. George Hope Ryder of New York city, owner of the Kelly collection of Civil war sketches.

* * *

Later this sketch was made into a finished drawing which was used for the tablet erected on the spot and dedicated on July 12, 1911. This finished drawing was first reproduced in the United States Army Recruiting News, by whose courtesy it is reproduced with this article.

* * *

When Lincoln stood on the parapets of Fort Stevens and watched the fighting, he little realized that a fellow-Kentuckian, who was an old political opponent of his, was watching the battle from the other side. Yet such was the case, for two of Early's divisions were commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, one of the Democratic candidates whom Lincoln had defeated in the presidential election of 1860.

During the attack on Washington, Early and Breckinridge made their headquarters at Silver

GEN. J. C. BRECKINRIDGE

Spring in the home of Francis P. Blair, famous as a member of Andrew Jackson's “Kitchen Cabinet” and editor of the Washington Globe, which was established at Jackson's request as the official administration newspaper. Blair and Breckinridge were cousins and before the war Breckinridge had often visited in the Blair mansion at Silver Spring.

So he saw to it that Early's soldiers did not molest Blair's private correspondence, consisting of letters from Jackson, Henry Clay and other notables, which had been left in the house. He even had Blair's silver plate transferred to another house for safekeeping and sent a note to Blair telling him what he had done.

However, the home of Blair's son, Montgomery Blair, postmaster general in Lincoln's cabinet, did not escape so easily. It was burned to the ground by Early's soldiers.

There is an amusing story of how they captured two game cocks owned by the Washington correspondent of Horace Greeley's New York Tribune. Although gamecocks are not the most toothsome kind of chicken, the Grayjackets are said to have taken unusual delight in boiling and eating the two which had been owned by “Old Horace's” representative!

After Early's departure a volume of Lord Byron's poems was found in which a Confederate soldier had written this message to the President: “Near Washington, July 12, 1864. Now, Uncle Abe, you had better be quiet during the balance of your administration. We only came near your town this time to show you what we could do, but if you go on in your mad career, we will come again soon, and you had better stand from under. Yours respectfully, The Worst Rebel You Ever Saw. Fifty-eighth Virginia Infantry.”

Lincoln the Only President Ever Under Enemy's Fire While Holding Office of Chief Executive; It Happened at Fort Stevens Just 75 Years Ago., Western Newspaper Union, Carbon County News, Red Lodge, Mont., July 7, 1939, Page Two. (PDF)

This article also appeared in: The Cambridge City Tribune, Cambridge City, Indiana, July 6, 1939, Page 2.

And in: The Pueblo Indicator, Pueblo Colorado, Jul 8, 1939, Page 3.