Key of All Keys

Mr. Hugh T. Taggart Dissects the Tradition of Braddock's Rock.

Asserts That He Did Not Land There.

Shows Where the Troops Probably Disembarked.

Of Historic Interest

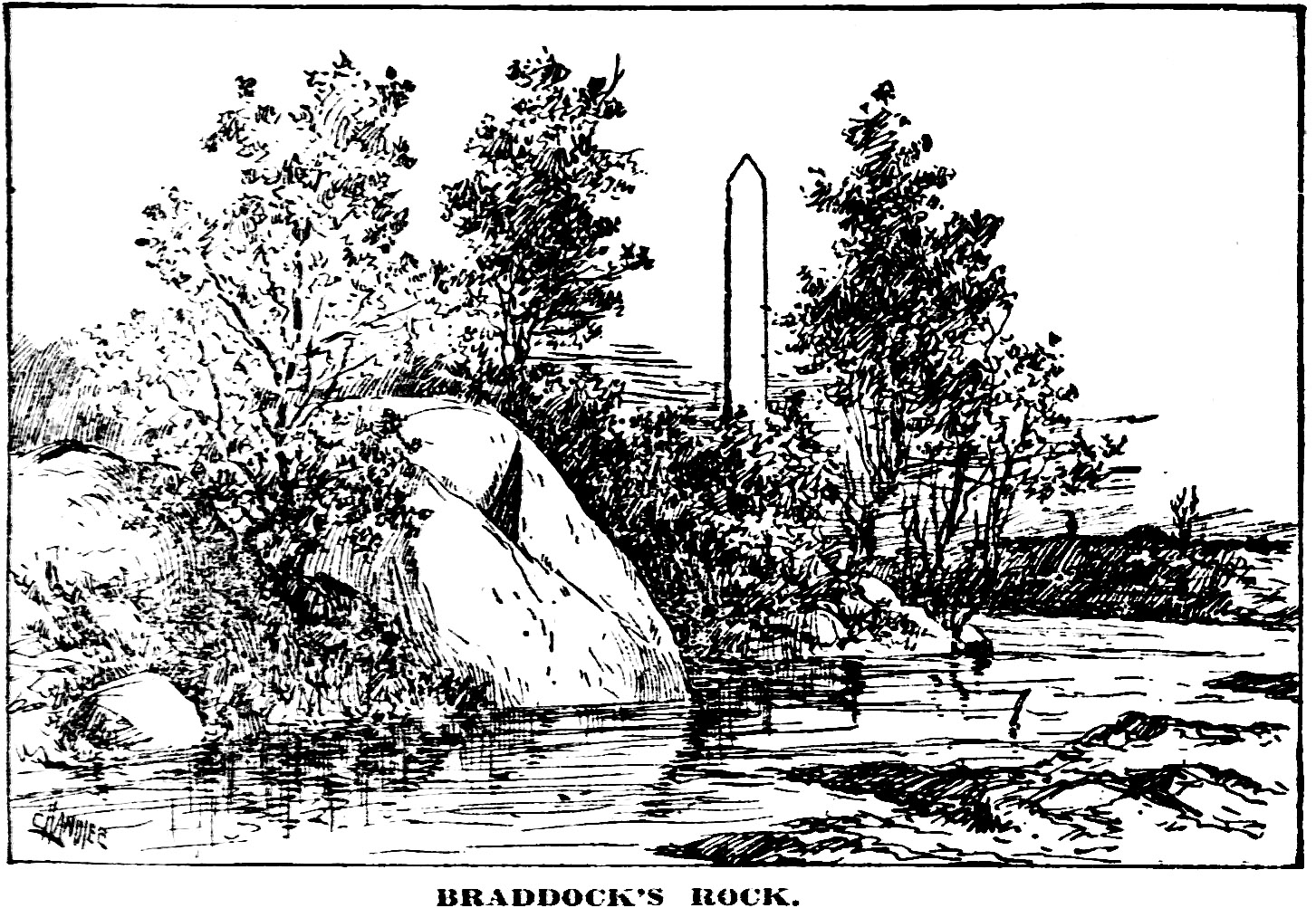

In The Year 1791, when the surveys were being made for the plan of the proposed federal capital, a large rock formed part of the shore of the Potomac river, and stood about midway between the points where 23rd and 25th streets met its waters. This rock was of considerable length, and it rose sufficiently high above the surface of the river to make it a picturesque and interesting feature of the landscape.

One portion of it extended for a considerable distance out into the river, presenting the appearance of a wharf or landing place; to this circumstance, and to the further one that there was a great depth of water at the rock, must be attributed the fact that it received from the first settlers the name of “The Key of all Keys,” that is the quay of all quays, or the greatest of all landing places. By that name it had become known soon after the arrival of the first Maryland colonists in the year 1632; by whom it was christened we know not, and history also leaves us to inference and conjecture as to the extent to which it was used for the purposes of which its name is suggestive.

It was anciently described as “a large rock lying at and in the river Potomak, commonly called the “Key of all Keys,” and being regarded as an imperishable monument it became an important boundary mark for lands in its vicinity. One of the earliest grants made by the colonial authorities in this section is that of “The Widow's Mite.” which was patented in the year 1686 to William Langworth.

This certificate states that a survey had been made of the tract, and both it and the patent give a “cedar tree” as its beginning; in after years, however, it seems to have been settled that the tract had for its beginning the rock known as “The Key of all Keys,” and this was its accepted starting point in the year 1791. It was doubtless intended to grant to Langworth, senior, a tract of land in this vicinity, but it is impossible to read the ridiculous errors of geography perpetrated in the description of the land given in the so-called certificate of survey without coming to the conclusion that the lines of the tract were not run on the ground at all.

Peter's Hill.

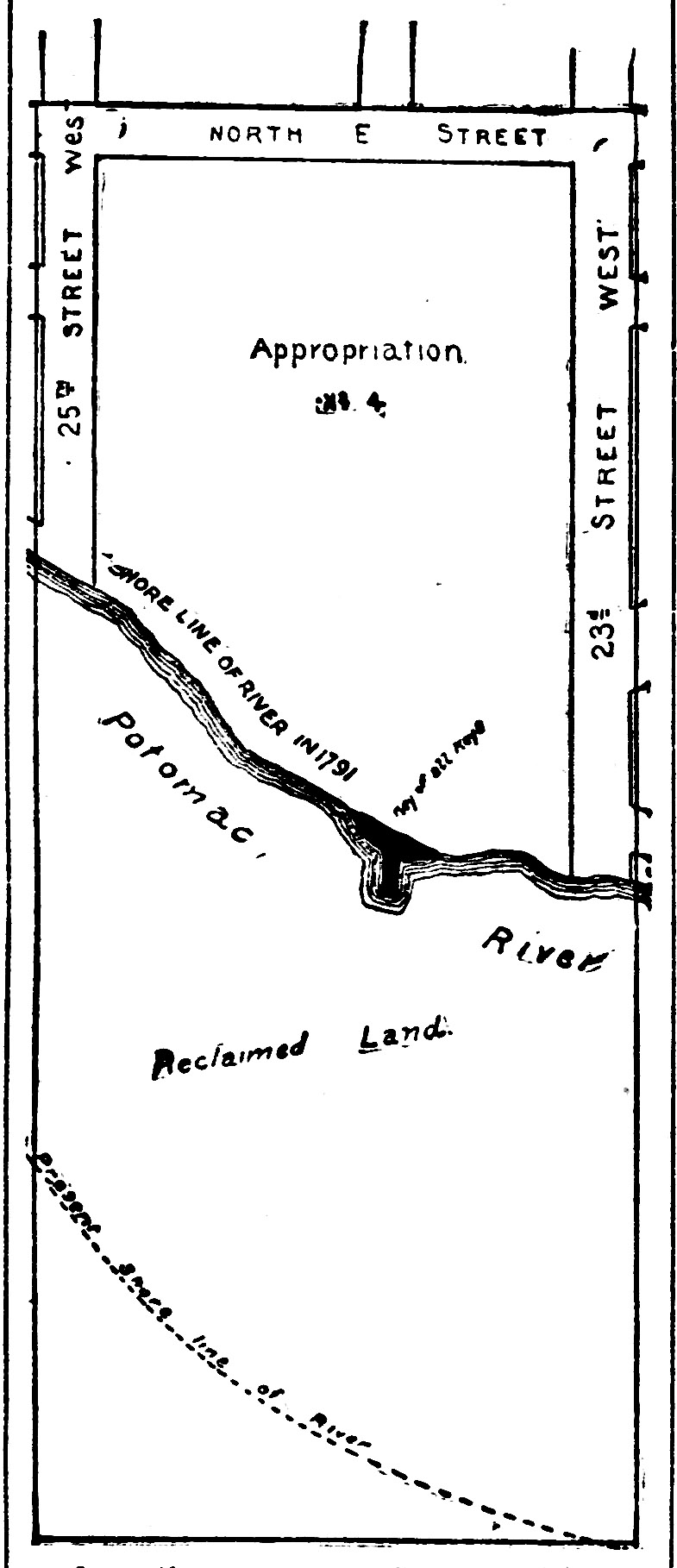

A large portion of the 600 acres included in the grant for “the Widow's Mite” fell within the limits of the city of Washington; the tract extended from the river side in the form of a parallelogram In a north westerly direction beyond the present northern boundary of the city, and the western boundary line of the tract nearly bisected one of the reservations made for public purposes by the government authorities, of land within the limits of the city, namely, the reservation between 23rd and 25th streets, having E street for a northern boundary and the river for a boundary on the south; this space, called “Peter's Hill,” was intended by the founders of the city as the site of a fort and barracks; it was later determined to locate upon it a national university, toward which President Washington contributed what was considered to be a “liberal pecuniary donation,” of fifty shares in the Potomac Company, then engaged in an effort (which promised to be successful) to improve the navigation of the river to a point far above the city (and convenient to the western waters), through the construction of canals around the various falls, the removal of rocks, etc. By the improvement it was expected that the trade of “the rising empire west of the Alleghanies” would be attracted to the Potomac. During the war of 1812 the militia encamped upon it, and Gen. Williams had there his headquarters, from which it became known as “Camp Hill.” A naval observatory was finally erected upon the site.

The “Key of all Keys” had an undisturbed existence until the year 1794; the commissioners of the city, who were then engaged in the construction of the Capitol and other public buildings, were embarrassed in that year by what would be called in this day a “corner” in foundation stone; they say in a letter to the President, dated December 23. “the price was risen upon us, nor could we lately form a new contract or get an old one renewed to our satisfaction.” They were indebted apparently to the “Key of all Keys” for relief, for in the same letter they announce “a discovery of foundation stone” at that place which they expected would prove to be valuable, and say that they had agreed to let Mr. James Greenleaf, who was then extensively engaged in building on his own account, have the use of a part of it.

The quarry was worked at their joint expense until July 20. 1794. when the supply of stone for the Capitol became insufficient through the neglect of its managers; there upon Cornelius McDermott Roe, under whom the work at the Capitol was progressing, took charge of the quarry and thereafter operated it upon the public account alone.

The Rock of Today.

The opening of this quarry no doubt resulted In the disfigurement of the appearance of the ancient rock, and by the construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio canal, in 1832 and 1833. it was completely demolished. The tow path of the canal was constructed beyond the line of the rock, and in the channel of the river. This left the rock in the bed of the canal, and its removal was accomplished by blasting. The only vestiges of it now remaining are three small ledges, which are still visible on what was formerly the berm bank of the canal. The place is now a dumping ground, filled with ashes, tin cans, broken glass, mounds of dirt everywhere and other unspeakable debris and refuse of a highly civilized community. On the occasion of a visit to the spot by the writer a few days ago a greatly inebriated Individual was stretched at length upon one of the ledges of the historic rock, profoundly engaged in sleeping off the effect of his potations. The continued use of the spot as a dumping ground will in a very short time result in the total obliteration of even the remnants of the rock which are now visible. The construction of the canal, followed by the reclamation of the flats effected an extraordinary change in the original shore of the river at this point. The shore line is now upward of quarter of a mile distant from the spot where tide formerly ebbed and flowed.

Interest In the old rock has been revived recently through the action of the local society of the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. It has long been a tradition in this community that the army of General Braddock, to which the father Of his country in his youth was attached as an aid-de-camp to the general, landed there and encamped On the Observatory Hill.

It was adverted to by so eminent an authority in matters of history as the late Peter Force; and George W. Hughes, civil engineer and superintendent of the Long bridge, in a report to the Secretary of the Treasury, dated January 30, makes this statement: “It Is matter of history that General Braddock disembarked at a rock, which still bears his name. near the glass house, from a sloop-of-war, on his unfortunate expedition against the French and Indians in 1755.”

Only a Tradition.

Upon the assumption that such was the fact, the society determined that it would be proper to mark the spot in a way to commemorate the event. The assertion or assumption that Braddock and his army landed on this rock in their progress westward from Alexandria can be established by no contemporary record and has to sustain it no basis of authentic fact; it has not the force even of probability to support it. The rock was undoubtedly there at the time, and might have been required by the expedition as a landing place had it been required by the necessities of the occasion.

It is a graceless task to destroy the romantic legend, but the undoubted facts of history are utterly inconsistent with such a movement by Braddock's army as will be readily seen from a review of the local situation at that time and of certain facts connected with the army which have been preserved.

In the valuable contribution to the history of the Potomac valley by our fellow townsman, William H. Lowdermilk, entitled “The History of Cumberland,” and in another work by Winthrop Sargent, entitled “The History of Braddock's Expedition,” will be found all the information extant in regard to the cause which led up to the expedition and of its movements on this continent. Mr. Lowdermilk's work contains the “Orderly book” of Gen. Braddock, printed from the originals in Washington's handwriting, which are in the Library of Congress; and that of Mr. Sargent contains the journals of Capt. Orme. and of the seamen detailed by the British admiral to accompany the expedition.

The story of the expedition, apart from local incidents and associations, is one of the most interesting chapters in American history.

The French being in possession of Canada and of the country at the mouth of the Mississippi and claiming the intervening territory by right of discovery, began the struggle “for the mastery of the continent,” by establishing forts at Niagara and Crown Point and attempting to establish a chain of posts along the Ohio and Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. Their aggressive movements were viewed with alarm by the British colonists along the Atlantic seaboard, by whom the French pretentions were denied, but the efforts of the colonists at resistance were feeble and without success; the French reached the junction of the Ohio and Monongahela, the site of the present city of Pittsburg, and captured a small detachment of Virginians. who were engaged there in the erection of a fort; they then erected a fort at the spot, to which was given the name Du Quesne, In honor of the governor general of Canada. A movement under the command of Washington culminated in disaster, and after the British flag was struck at Fort Necessity, and Washington's little army retired. “the lilies of France floated over every fort, military post and mission from the Alleghanies to the Mississippi.”

The English Aroused.

The government of Great Britain became aroused, and money was appropriated by parliament to defray the expenses of an expedition having for its object the restoration of English power on the continent. On September 24, 1754, Sir Edward Braddock was commissioned by King George as general of all the troops to be sent to North America or raised there; under date of November, 25, 1754, he received his instructions from the king, which read in part as follows:

“1. We having taken under our Royal & serious consideration the Representations of our subjects in North America, & ye present state of our colonies, in order to vindicate our just Rights and Possessions from all encroachments, & to secure ye Commerce of our subjects, We have given direction yt Two of our Regiments of Foot now in Ireland, commanded by Sir Peter Halket & Col. Dunbar, & likewise a suitable Train of Artillery, Transports and Store Ships, together with a certain number of our Ships of War, to convey the same, shall forthwith repair to North America.

“2d. You shall immediately upon the receipt of these our instructions embark on board of one of our Ships of War, and you shall proceed to North America, where you will take our said force under your command. And We having appointed Aug. Keppel, Esqr., to command ye Squadron of our Ships of War on ye American Station, we do hereby require & enjoin you to cultivate a good understanding & correspondence with ye sd Commander of our Squadron during your continuance upon ye Service with which you are now entrusted. We having given directions of ye like nature to ye Sd Commander of our Squadron with regard to his conduct & correspondence with you.”

Braddock in Command.

The king further directed that the complements of the two regiments of foot should be increased from 500 to 700 men each, by recruits to be enlisted In America, and that two other regiments of foot of 1,000 men each should be raised in the colonies, one of which should be under the command of Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, and the other of Sir William Pepperill. Sir John St. Clair was appointed deputy quartermaster general of the forces.

Braddock was given the chief command in America upon the recommendation of the Duke of Cumberland, the British commander-in-chief, from whom he received further instructions enjoining him among other things, to constantly observe strict discipline in the troops, “and to be particularly careful that they be not thrown into a panic by the Indians, with whom they are yet unacquainted and whom the French will certainly employ to frighten them.” As shown by the sequel, this injunction was not regarded by Braddock, for he was ambushed by the French and Indians on July 9, 1755, and his army destroyed.

Walpole describes Braddock as a man “desperate in fortune, brutal in his behavior and obstinate in his sentiments,” but “intrepid and capable.” Shirley described him as “a general most judiciously chosen for being disqualified for the service he is embarked in, in every respect.”

Lowdermilk, in a review of his character, states that “he was fond of high living, convivial and prone to the laxity of morals that usually follows excess in those partlculars. The gaming table had its fascinations for him, and he was arrogant, unforgiving and intemperate. He was haughty, severe, reserved and full of self-importance, which qualities served on many occasions to make him greatly disliked. There was little of refinement in his nature. and he was brutal in his treatment of those who invoked his resentment or dislike.”

Landed at Alexandria.

Braddock left England on the 21st of December, 1754, on the Norwich, Capt. Barrington, accompanied by the Centurion, the flagship of Commodore Keppel, and the Syren, Capt. Proby. The fleet which transported the expedition to America consisted of the transports Anna, Halifax. Osgood, London, Industry, Isabel and Mary, Terrible, Fame, Concord, Prince Frederick, Fishburn, Molly and Severn. There were also two ordnance ships, the Whiting and the Newall, the whole under convoy of two men-of-war, the Seahorse and Nightingale.

Upon the arrival of the vessels in Hampton Roads they were directed to proceed to Alexandria or Belhaven, where the troops disembarked and went into camp.

Sir John Sinclair advised the general that by making two divisions of the troops Fort Cumberland on Willis creek (the site of the present city of Cumberland) might be reached with more ease and expedition. He proposed that one regiment with all the powder and ordnance should go by way of Winchester and the other regiment, with the ammunition, military and hospital stores, by way of Frederick, Md., and he assured the general that boats, batteaux, canoes and wagons were prepared for the service and also that provisions were laid in at Frederick for the troops.

These recommendations were approved and acted upon, and on the 9th of April, 1755, Sir Peter Halket, with six companies of the forty-fourth regiment, marched to Winchester, leaving Lieut. Col. Gage with the other four companies to escort the artillery. Capt. Orme states that boats were not provided for conveying the stores to Rock creek and the general was obliged to press vessels and to apply to the commodore for seamen to navigate them, and that finally and with the greatest difficulty they were all sent up to Rock creek and an officer with thirty men of the forty-eighth regiment was sent thither with orders to load and dispatch all the wagons as fast as they came in.

At Rock Creek.

The officer was directed to send a party with every division and to apply for more men as the others marched, “and all the boats from that part of the river” were ordered “to assist in transporting over the Potomack the forty-eighth regiment.” On the 14th a council was held at Alexandria, at which were present Gen. Braddock, Commodore Keppel, Gov. Shirley of Massachusetts. Lieut. Gov. Delancy of New York, Lieut. Gov. Dinwiddle of Virginia, Lieut. Gov. Sharp of Maryland and Lieut. Gov. Morris of Pennsylvania. On the 18th the forty-eighth regiment marched to Frederick, leaving thirty additional men with the officer at Rock creek.

The business of the council being over, Capt. Orme states that the general would have set out for Frederick, but few wagons or teams were yet come to remove the artillery. Of this he advised Sir John Sinclair, and a few days thereafter set out for Frederick, leaving Lieut. Col. Gage and the four companies of the forty-fourth regiment with orders to dispatch the powder and artillery as fast as horses and wagons should arrive. At Rock creek the general called for a return of the stores and gave orders that such as were most necessary should be first transported.

On April 11 a detachment of thirty seamen from the fleet were provided with eight days' provisions and ordered to pro

ceed on the morrow to Rock creek, eight miles, in the boats of the Sea Horse and Nightingale; in their Journal it is recorded that they arrived at the creek at 10 a.m. of the 12th, and, finding Col. Dunbar there, placed themselves under his orders; on the 13th they were employed in getting the regimental stores into wagons, the situation is said to have been pleasant, “but provisions and everything dear;” they began the march at 6 a.m. of the 14th, and camped at 2 o'clock in the afternoon at the ordinary of Lawrence Owens, “fifteen miles from Rock creek and eight miles from the upper falls of the Potomack;” on the 17th they arrived at Frederick, which, although “not settled above seven years,” it is said, had “about 200 houses and two churches, one English and one Dutch,” and that the inhabitants, chiefly Dutch, were an “industrious but imposing people.”

Route of the Expedition.

From the “Orderly Book” it appears that on April 7, 1755, Col. Dunbar's regiment (the forty-eighth) was directed “to March at 6 o'clock on Saturday morning for Rock creek,” and “all boats on that part of the river near Rock creek are ordered to attend to carry the troops over.” The route of march was prescribed: To Rock creek, eight miles; to Owen's Ordinary, fifteen miles; to Dowden's Ordinary, fifteen miles; to Frederick, fifteen miles.

It further appears from the “Orderly Book” that on April 8 an officer and thirty men were directed to remain at Rock creek “till all the stores of the train and hospital are put into the wagons,” and then “to march and form a rear guard for the whole;” that on April 9 two sergeants and twenty men were ordered to the creek “to reinforce the officer there;” on the 11th the fact is noted that boats had been provided “to carry Col. Dunbar's regiment's baggage to Rock creek;“ the time of the march was postponed, and by the orders of April 25 the regiment were directed “to hold themselves in readiness to march by the 20th;” there is no entry for the 29th, but doubtless the regiment marched on that day agreeably to the orders; under date of the 28th are entered the final orders to Ensign French, the officer at Rock creek.

Washington seems to have had no connection with the expedition, and did not accompany either of the columns on their march from Alexandria; his name is first mentioned in the orderly book on May 10, 1755, at which time the army was encamped at Fort Cumberland. The entry is as follows: “Mr. Washington is appointed aid-de-camp to his excellency General Braddock;” it was evidently after this that he entered the orders of a previous date.

The Journals of Capt. Orme and the seamen show that Braddock did not accompany Col. Dunbar's regiment when it marched to Rock creek, and, as has been indicated, Washington only became connected with the expedition after its arrival at Fort Cumberland, and was not with it on the march from Alexandria to Rock creek; they further show that the movement of the regiment was overland from Alexandria to a point somewhere on the Virginia side of the river nearly opposite Rock creek, from which it was transported in boats to the Maryland side, and that the baggage was transported to Rock creek by water.

Where the Landing Was Made.

It only remains to be determined whether the landing upon the latter side of the river of either baggage or men or both was made at “The Key of all Keys.”

There is historical evidence, the authenticity of which is beyond dispute, and by which the question is settled conclusively in the negative, as to both baggage and men.

The act of the Maryland assembly which provided for the laying out of Georgetown was passed in December of the year 1751; It recites that several inhabitants had represented to the legislature that there was a convenient place for a town on the Potomac river, above the mouth of Rock creek and “adjacent to the inspection house.”

As early as the year 1640 the colony had by its legislation provided for the inspection of tobacco, and forbidden its export until it had been “viewed and inspected;” the vestries of the different parishes were authorized to appoint the inspectors, and numerous warehouses were erected by individuals near navigation, at which the tobacco was collected and the inspections made.

On October 4. 1748, the vestry of Prince George's parish appointed Capt. Alexander Magruder, Messrs. Josiah Beall. John Clagett and Alexander Beall as the inspectors for “George Gordon's warehouse at the mouth of Rock creek.” Georgetown was laid out around this warehouse; its site was known as the “Warehouse lot,” and upon it now stand the buildings of the Capital Traction Company, formerly the Washington and Georgetown city railroad, which front on the south side of Bridge street near High street. These inspection houses, at or near shipping points, became centers of trade, and the principal roads in their vicinity led to them and to the landing places.

West of the Creek.

In 1751 the main roads leading to the site of the town and Gordon's warehouse were the road to Frederick and the road to Bladensburg, the latter of which crossed Rock creek at the ford and just beyond the present P street bridge. The road to Frederick followed the river for some distance above the town, and vestiges of it seem still to remain along the canal, near the present Cabin John bridge.

The objective point being Frederick. It was along this road that the forty-eighth regiment of Foot marched; It could not be reached by any road from “The Key of all Keys” without ferriage over Rock creek, or by a circuitous route by way of the ford. It must, therefore, be assumed that the regiment crossed the river west of the creek.

Since 1751 a great space has been reclaimed from the water on the Georgetown side of the creek, but when the town was laid out in that year Its southeastern corner or boundary was very near the creek, and at a place called “Saw Pit landing.” In 1755, when Braddock's regiment passed, this landing was still in existence.

The map of Jefferson and Fry, published in 1777, was based on surveys made between 1748 and 1755; it shows Rock creek and a place on the Maryland side, about opposite the western end of Analostan Island, which bears the name of “Magee's Ferry.” All indications point to the road to the ferry landing on the Virginia side as the one traveled by the regiment in its march from Alexandria, from which transportation directly across the river alone was needed to reach the road to Frederick; this road no doubt extended easterly to Saw Pit landing, which point would have been the most convenient one for the landing of the baggage, and for this reason it may have been used for that purpose.

Washington Landed There.

It is quite likely that Washington used this rock as a landing place while pursuing the occupation of his youth, in making surveys of lands along the Potomac for Lord Fairfax and others, or upon the occasion of a friendly visit to a Maryland neighbor during the early days of his residence at Mount Vernon, but “The Key of all Keys” had no association with Braddock's expedition beyond that of propinquity to one of its lines of march.

Independently of this, however, the ancient rock was a historic spot for the reasons which have been stated, and for the further reason that it became one of the boundary marks of a town laid out in 1767 by Jacob Funk, under the name of Hamburg, but which was more generally known as Funkstown, and which lost Its identity when the federal capital was established, within whose limit's the town was included.

Although in the work of reclaiming the flats the shore has been pushed far away from its former location at this point, a pond has formed in a depression along the ledge of rocks, which constitute all that remains of “The Key of all Keys;” the pond is mostly given over to such uses as frogs and small boys can find for it; the writer recently observed one of the latter launch a toy boat into this pond from one of the remains of the rock; the boat moved over the surface of the water in the most approved propeller fashion. Closer examination of the boat showed it to be about twenty-two inches In length, of graceful outline, and that it was provided with a rudder and screw, which latter was worked by machinery; and inquiry developed the fact that the small boy, Master Willie Sribner, who owned it, was an exceedingly bright and intelligent specimen of his class, and that he was withal of an ingenious turn of mind; that he had cut the boat out of a solid block of wood, and supplied it with a rudder and screw, also of his-own manufacture, and that its motive power was due to the works of a clock, which he had adapted to the purpose and introduced into its hold. The observer could not help making a mental contrast between the pastime of this boy and that of his predecessor, the Indian small boy of the remote past, whose lessons in the art of navigation begin and ended with his bark canoe; and a cogent reason for the failure of the latter to maintain himself in the struggle for existence, which was precipitated upon him by his white brother, was apparent.

It is thought that the foregoing furnishes considerations of sufficient importance, even in this utilitarian age, to require that the destructive hand of man be stayed, and that the remnants of the ancient and historic rock should be rescued from the oblivion with which they are threatened and their existence perpetuated as a memorial of the past, and it is to be hoped that the city fathers may take this view and at once adopt such measures as may be necessary In the premises. If anything is to be done circumstances demand that it be done quickly, in order to save from an ashy grave what remains of “The Key of all Keys.”

Hugh T. Taggart.